Celiac.com 09/29/2022 - The book Gluten-Centric Culture is the result of a nation-wide study of gluten-sensitive adults living with other adults. Previous gluten-related studies primarily examine children. This is one of few that focuses entirely on adult social experiences. As we have seen in earlier chapters, cultural practices make life difficult for those avoiding gluten at any age. The chapters have detailed how cultural constraints such as exclusionary etiquette rules make it challenging to both be polite and dodge gluten at the dinner table. Other cultural constraints such as able-bodied biases are illustrated when only gluten-containing foods are offered, and when special needs are not considered. We’ve seen how “gluten” is the butt of jokes, causing our requests to be mocked and often making us doubt whether supposedly “gluten-free” foods presented to us are safe to eat.

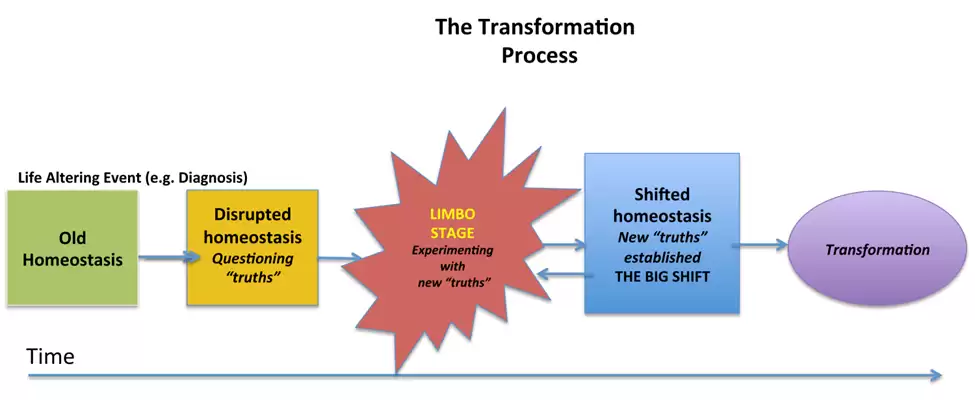

In Chapter 2 and Chapter 4, we learned how some in the medical community aren’t adequately trained to correlate physical symptoms with gluten consumption, resulting in mis-diagnoses such as brain tumors, stomach cancer, or mental illness, illustrating the I-know-best attitude. We’ve seen how women in particular are often victimized by sexist scrutiny in Chapter 5. In Chapter 6, we illuminated the Disease Process and how a newly diagnosed person goes in and out of “limbo” as “truths” form, eventually evolving into a new homeostasis using new “truths” in every aspect of life. This ultimately leads to the final phase of the disease process called “transformation.” The present chapter expands the transformation stage, where a person with gluten sensitivities or celiac disease can press the “replay button” on scenarios that didn’t work before. Here, we apply the new awareness gleaned from reading this book, incorporating the language, breaking down cultural constraints, and living with a feeling of empowerment.

A Gift for You

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

Before getting started, I’m taking applications and will choose three people who will receive free admission to one of the Cultural Constraints workshops that take place in October as a “thank you” to my readers. If you are struggling with some aspect of the food sensitive lifestyle, the workshop is designed to review a few constraints and roleplay how we might prevail. Once we have language and have cultivated an attitude of being empowered, we can command respect. Not understanding these cultural practices results in people feeling isolated from social events. Living the gluten-free lifestyle is a social disease (Bacigalupe, 2015), but it doesn’t have to be. Understanding is the first step to thriving in life. To apply, please click here to access the application form.

Pressing the "Replay Button"

In previous chapters, we’ve discussed language to broach a conversation. Just as we do when thrown into the limbo stage when experimenting with alternative approaches to a social conundrum (Chapter 6), let’s try pressing the replay button in some of the scenarios we’ve already heard about. In Chapter 5, we assessed that Gianna’s (#50) living situation indicates an absence of agency. She does not have the power to ask her husband to amend his jelly-slathering ways in order to protect her from cross-contamination. What if Gianna embraced concepts of respect and compassion and said to her husband: “Honey, every time I eat anything in this house, I feel the effects of gluten. I’m sick of being sick, and also it frightens me because I know that if I expose myself to gluten, I can develop some of the long-term illnesses associated with celiac disease. How can we work together to come up with a solution so that you do not contaminate me in my own house? This conversation asserts agency and respect. Commanding agency in a relationship is risky because people generally don’t want to deal with change or assertiveness from someone who, until now, hasn’t been assertive. It is terribly hard to do this, particularly in a long-term relationship. It may expose that her husband has no intention of cooperating on that, or any other need Gianna may have. It may trigger her husband to list a litany of things he isn’t happy with in the relationship, changing the focus from Gianna’s concerns to his own. Rather than being constructive, her husband may initiate a behavior that quells Gianna from further discussing her needs. Ultimately, it may force Gianna to make some difficult decisions. On the other hand, it is very empowering for Gianna to ask that her needs be met and that her health is valued. She is commanding respect and this is an empowering step toward transformation.

We also identified that in this scenario, Gianna’s husband was operating from the I-know-best attitude. Perhaps if Gianna gave him some literature that pointed out the ill-effects of gluten consumption for those with celiac disease, he would change his mind about being so careless in the kitchen. Now, I know it may fall on deaf ears. Some people you live with are locked into the I-know-best, gluten-doubt, and able-body bias frames of mind no matter what you do! Many of these people simply lack the knowledge of how to be compassionate. I believe compassion is a learned skill, and providing examples to people on how to be more compassionate goes a long way. For example, asking someone to say, “I’m sorry you have to live with this and I’ll do everything I can to support you” gives reassurance and loving concern. Or saying, “We’re all in this together” as described by Brenelle (#56, Chapter 6) is kind. Brenelle felt supported and respected by her family members. They created a safe environment where she could thrive. But whether it works or not, by taking the initiative to have the conversation, Gianna asserts her needs and defies her husband’s I-know-best attitude. She is taking control of her situation and testing alternatives while in the limbo stage.

Another illustration comes with Julia (#49, Chapter 4), whose father said, “if you are so restrictive, why are you so chubby?” Rather than debating with her father, her response to his comment was to only eat very few safe foods. She describes being hungry most of the time, and seething in anger with her father’s judgment. This shows dysfunction in the relationship, putting Julia in a constant state of limbo. She can’t thrive until she works this out. Let’s hit the “replay” button on Julia’s scenario. What if Julia said to her father: “I really need you to understand what it means for me to have celiac disease. It means that I cannot eat anything that contains gluten. Do you know what gluten is? It’s a protein found in barley, rye, oats, wheat, and spelt. It is also in nearly every processed food, and any little amount of it makes me sick. Remember when I went to the doctor and was diagnosed? That’s what they told me. I really need your cooperation. I might be chubbier than you think I should be because my body doesn’t work properly. I am eating anything I can find that I know is “safe” and not all of those “safe” choices are high-quality foods. I want to get well, and I want to exist in harmony with you. Would you please help me to avoid gluten?” This shifts the dynamic in the father-daughter relationship. Before, Julia was victimized by her father’s cajoling. By saying these words to her father, Julia exerts agency. It empowers her to restate her needs in the future. Even if her father doesn’t relent, she is taking ownership of her needs, and ultimately this might lead Julia to having more self-confidence. I’m not saying it will change the way her father acts, but taking this initiative begins to give Julia more control of her circumstances and privileges her to make positive changes for her own well-being.

Let’s hit the replay button on Cousin Sandra from Chapter 1. Instead of divorcing the family, which fills me with a profound sadness on her behalf, what if she had said, “I want to be a family member and to participate in these dinners and all of your conversations. I want to be included. I have a disease that prevents me from eating some foods and I feel safer bringing my own to these gatherings. When I ate foods prepared in your kitchen that should have been safe for me, I found that I became ill – likely from cross-contamination. I don’t want to have to be sick to be included. Rather than showing my inclusion by eating the same foods, how about if I bring my own foods and we dwell on our love for each other, relish being together, and not worry about whether I’m eating what you are?” And what if she actually took it a step further and singled out the person that was the most vocal about her special needs and asked him or her in front of the rest of the family, “Can I count on your support?” Would this have had the intended affect and changed the minds of some of those around the table? I don’t know, but I do know it would have given Sandra a different attitude about her dietary restrictions. I am sure there were many at the table that wanted her to continue to be a family member and were sorry when she left. If she had continued to show up with her bowl, and demanded with her actions that she was accepted into the realm, I think in time, nobody would have cared. Sure, she might have had to endure some teasing, but what family doesn’t tease each other about one thing or another? (Have you noticed though that those who tease can’t take it well when you tease them back? Just an aside observation.) It takes incredible courage, but if you can stand up to your family or the one ringleader in your life that has been making you miserable by asserting their power and ignoring your needs, you will be able to stand up to anyone. Being assertive about your needs permeates all aspects of life – rather than being apologetic, it shifts you to being self-accepting and requiring that others accept you too.

Sarah (#31) first mentioned in Chapter 3, lived in limbo when she was isolated on campus that first year because of the school’s thoughtless rule of disallowing her to comingle with gluten-eating cohorts. The school environment forced Sarah to confront the able-body bias, causing her initially to be a victim of the circumstance. Because of the school’s interpretation of the American Disabilities Act, she missed out on developing those ever-important freshman relationships that can last a lifetime. Rather than having gluten-free foods available in the dining hall, authorities at the school determined that the only way to keep Sarah safe was to isolate her in her own apartment where she could prepare her own meals. She was in stages of both food and social limbo (discussed in Chapter 6) as she crisscrossed the campus to find safe havens to eat, and endured the loneliness of not being able to celebrate and party with her classmates. She resolved her limbo-state herself by finding other people on campus that would honor her needs, and they became roommates and friends in subsequent years. Her initiative yielded a positive outcome from an otherwise difficult situation.

Claire (#25) from Chapter 3, was humming along in life until she re-entered into the limbo stage when she partook in the gluten-containing host on Sunday during communion in the church venue. She felt she had to participate in the communion ritual, eating the gluten-containing host to please the priest and to comply with the Pope’s edict; while at the same time, she suffered the consequences of being sickened each Sunday afternoon and feared the long-term effects of consuming gluten on a weekly basis. It was a dilemma that invoked the I-know-best attitude, able-body-bias, absence of agency, and gluten-doubt beliefs. Whew! That’s a lot to deal with, not to mention the higher-power guilt factor imposed by some religions. Couple all that negativity with a stomachache, and you can imagine what her state of limbo felt like – mentally and physically! If Claire reconsiders her decision to partake in light of these “truths” that are in play, she may decide not to consume the host, or she may approach the church and request that they accommodate her physical needs. When faced with the same gluten-containing host dilemma, Cora (#36) from Chapter 3 took control of the situation when she decided that she would only take the wine because “The Lord knows what is in my heart.” This is a very personal decision, but one that has to be ultimately resolved to avoid constant gluten contamination. By understanding the dominant powerful forces that cause us to feel pressured into participation, we can claim agency as to what works or doesn’t for us.

In the workplace, Ava (#7) from Chapter 3 showered, groomed, and dressed for work only to turn around and go home because she accidentally soiled herself. She endured humiliation when she had to explain this to her boss and co-workers who told her to take Imodium or visit the doctor. This illustrates the state of social limbo, which is an out-of-control situation, where you have no answers and when other aspects of life cascade as a result. Ava tried to explain to her I-know-best and gluten-doubting boss and coworkers to no avail, causing her to ultimately quit working there. Sometimes, that is the only answer to get out of limbo—to put an end to a bad situation. Hopefully, Ava can find a more flexible situation where this problem won’t interfere with getting her work done. Pressing the replay button is an important component of transformation. It provides alternative ways to deal with tricky social situations.

Transformation

Our identities evolve as we live under the veil of celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity. When we attend ceremonies, rituals, or engage in commensality with family or friends, we constantly have to remember, “I can’t eat that,” or, “I need to ask about the ingredients,” or “I have to prepare in advance the foods I’ll eat.” It weighs on us in every aspect of life in the beginning, but over time we adapt. We wear a new mantle of food awareness as we learn to live with the disease. Individuals transform themselves under their evolved identity (Charland, 1987). It is at this level where the formation of stories and new “truths” interact to ultimately transform the identity to answer the question: How do I adjust my gluten-free lifestyle so that I can thrive? When a person with an illness stops fighting, hiding, and denying her disease, and takes assertive and protective steps by disclosing as necessary, she has attained identity transformation. In essence, she “owns” the disease, considers it part of her reality and incorporates its demands into all aspects of life. When someone with a disease attains the state of identity transformation, she accepts it and expects those around her to respect her resolve. She has altered her belief system to accommodate her new situation. Her identity is reformed as a result of changes in mental and physical awareness. She has found a way to love her new set of circumstances.

She’s gone through the Big Shift (Chapter 6) to transformation. When the transformed individual thinks of her homeostasis “before,” she can’t believe how much life has changed. She even thinks differently! What she once held as sacred “truths” are now redefined. Foods she used to consider “normal” are not foods to her anymore. Pizza, which used to represent a fun celebration now looks like something that will cause her agony and pain, but that doesn’t bother her. She knows how to make a delicious gluten-free alternative that’s a lot healthier! She genuinely likes her diet of healthy, whole foods and she feels a million times better than she did when she ate gluten. Many of her younger friends can’t keep up with her energetically. She has endless energy, sleeps soundly at night, and wakes up pain-free, ready for the new day. She’s established new rituals with her family, and she has altered her ways to accommodate her needs. Things are mostly smooth. Occasionally, something happens that throws her back into the limbo stage, but those instances happen less and less often. She accepts herself and is no longer feeling at odds with the world around her because she has changed her attitude. She lives with confidence and self-esteem. She is not afraid to ask politely for what she needs, and she quit apologizing for her situation long ago. Life isn’t a series of food-conflicts anymore because she has surmounted the obstacles. She loves her new identity and the graceful living she has finally attained.

Positive Adaptations

Scarlet (#14) conveys an example of coming to terms with gluten-free constraints in describing her first post-diagnosis Thanksgiving. She reports she was initially stumped as to what to serve, so she made cheeseburgers without buns. To this day, her family jokes about that first Thanksgiving. Family adaptation is further illustrated in Sadie’s (#41) story: “We make [gluten-free food] a fun thing, to find places to go such as gluten-free bakeries when we travel, or places we wouldn’t otherwise go to when at home.” She describes gluten-free chocolate doughnuts her husband found at a bakery 40 miles away, and how he would occasionally get them for her as a treat. These adaptation stories illustrate positive ways families accommodate the needs of the person with celiac disease. In time, these stories become integrated in the family’s collective lore and new traditions replace food-centered rituals. For example, when reflecting on her relationship with her husband, Caroline (#28) says:

Food is a pretty central part of our lives. We both enjoy food. And we both come from families that have always nurtured with food. So, I am trying to shift that and find other ways to connect, and to show that we are nurturing each other without being so food-focused. We do a lot more outdoor activities, like hiking and biking. We used to be more indoors people up until that point. We are learning that together. When we want to be with friends, instead of going out, we have friends over, and I try to do a game night, instead of a food-focus night. Then, we can just have a couple of snacks versus a meal that most people would be unhappy with, if their favorite foods weren't involved.

Caroline describes her adaptive strategies for spending quality time with her husband and friends without involving food. She tells how they now do physical activities rather than centering social gatherings on food. Similarly, Willow (#30) describes how she consciously tries to remove the emotional connection to licorice and baseball, separating the gluten-containing licorice association from her enjoyment of a baseball game. After a few months of eating gluten-free, Madeline (#57) said, “Wow, I didn’t realize how sick I was,” connecting her diet with her newfound health. After several mishaps, Lillian (#58) has taken the helm to host Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners, so she doesn’t inconvenience her family members with her needs, and so she is assured of a safe gluten-free meal. She enjoys her new role as host. Scarlet decided to grow the foods she consumes in her garden. She discovered a fulfilling hobby, while also assuring that she has safe foods. These are just a few examples of how study participants transformed the way they view themselves, changed their rituals, and how they interact with friends and family.

Rewarding Transformations

For some participants, the gluten-free diet required by celiac disease provides a rewarding personal transformation. Those who are able to find “redemptive meaning” through transformation tend to be happier (McAdams & McLean, 2013, p. 233). For example, Allison (#35) describes her transformative story as follows:

When I was first diagnosed, I was well over 230 pounds. I gained 60 or 75 pounds in a year. I was so sick. Once I was put on the gluten-free diet, I immediately felt a change in my body. I lost weight. I was feeling great, and I had a lot of energy. I have lost well over 50 pounds and 21 inches. And I am still losing! I am pretty thankful I’ve gone from a size 20 to a size 12. I’m happy with the results. I am definitely an advocate for getting diagnosed with celiac disease because I can understand the frustrations and the feelings and emotions and the cycles that you go through. Because when you stop eating gluten, you are grieving, and it’s like you’ve lost a loved one. It’s a whole new lifestyle.

In this story, Allison describes the grieving process and then the personal satisfaction from being on the gluten-free diet. Her transformation was rewarded with a healthier body and lifestyle. Similarly, Sally (#3) describes a positive physical transformation as a result of accepting the diet and constraints of the disease:

You know, it’s something I had to go through to become who I am today, and in a lot of ways, I’m a much better person than I ever have been. I mean, I eat better. I may still be overweight, but I’m getting my leaky-gut syndrome taking care of and that’s going to eliminate a lot of my issues. I appreciate the things a lot more in my life now than I ever have. And I suspect that I had celiac disease for about 10 years before I was even diagnosed. But something changed about four or five years ago, and it went from small issues to major issues.

Sally’s weight and physical health improved after eliminating gluten, enhancing the quality of all aspects of her life. Sally’s positive metamorphosis illustrates a common sentiment expressed by other study participants as they realize how much better life is with a healthy body. Forty-five-year-old Hazel reports she first attributed her physical ailments to aging, saying, “I decided that was part of getting old...like I felt like I was about 70 years old.” After being gluten-free for a while, she commented on how much better her body felt, and how much more she was able to do with it. She went from surrendering to “old age” to feeling “young” again. Correspondingly, Claire (#25) notes, “I am thrilled. I am eating healthier, and I also noticed I was more relaxed now that I got off the gluten.” Claire’s outlook on life changed from being anxious about everything to having a calmer demeanor. And Lucy (#26) describes her post-gluten transformation as follows, “I have increased energy, and symptoms I had my whole life—like abdominal pain, fatigue, and constipation—are gone. I slowly felt better and now have a lot more energy and a lot less illness in general.” Lucy enjoys a more physical life than she did before she stopped eating gluten and feels she has regained her health. My surgeon father-in-law, Jacob Peretsman reminds us: “When you have your health, anything in life is possible.”

Creative Transformations

Hazel (#22) describes how her life changed after being diagnosed with celiac disease. She reports, “I used to be a chef. And I have a really, really strong intolerance to gluten. I actually react tactile: if I touch it, my hands peel. So it changed my whole life. It changed everything about my life.” Hazel was no longer able to perform her trade of baking gluten-containing foods and had to relearn how to bake. Hazel’s example illustrates the entire arc of transformation. Her liminality or “limbo” stage occurred when she realized it was gluten causing her hands to peel. She describes how devastating it was to learn that materials she used for the skill she worked so hard to cultivate were causing her to have problems. She experienced the fear of being unable to do her job. Her life was upended, as she worked out a solution. But her homeostatic shift included learning to bake without gluten, while using her culinary skills. Her identity transformation occurred when she declared herself to be a gluten-free baker. Hazel makes gluten-free bread for her Mormon sacred communion and shares it with others in the congregation who are gluten-free. Her positive transformation was reinforced when her son said: “Mom, you make gluten-free food taste good.”

Other participants talked of how they adapted. For example, Riley (#65) now makes a lovely, soft gluten-free bread from a recipe she found on the Internet and sells it at the local farmer’s market. She says: “It has been a really nice experience, especially when people who eat gluten want to try your food.” Isla (#39) reflects on a kind gesture from her brother. He had the bakery put several frosting roses into a separate bowl for her to eat, so they wouldn’t be contaminated by the cake. She felt his kindness indicated his full acceptance of her disease, and he was helping her to still be able to enjoy some “normal” aspects of a birthday party. Carrie (#4) describes how her once rebellious family now enjoys eating the same gluten-free foods she prepares for herself, especially her desserts. In fact, they say they like her gluten-free food as much as they like gluten-containing desserts.

Cara (#53) was diagnosed along with her two sons. She describes how she brings similar gluten-free dishes to social engagements for her family to consume. Someone at one of the potlucks said, “How blessed your boys are that you are their mother, and how hard this would be if you didn’t have the positive attitude you have.” That comment made Cara feel like she achieved a milestone because she was recognized for her unique talents to make tasty foods for her sons and herself. She also felt accepted by the potluck attendees. These examples illustrate how participants became comfortable with their new homeostasis and identity transformation.

Snags After Transformation

A friend of mine, Margaret described how she changed her ways after her transformation only to hit a snag. They decided a few years before to stay in a hotel when visiting family and friends so that Margaret could prepare her meals in a safe environment without having to disrupt the flow of the household. This worked for several years. She and her husband, John were planning to visit her in-laws for Christmas. This time, John really wanted to stay in his parent’s newly remodeled home. It also meant a lot to his mother, Milly for them to stay under one roof to have quality family-time. Margaret briefly went back into the limbo stage and worried this would cause a host of problems for her because no one in the family is gluten-free. John’s family members have shown reluctant tolerance and I-know-best attitudes toward her before – particularly Milly – the territorial captain of the kitchen who really doesn’t like sharing it with anyone.

After hearing my Thanksgiving story (Chapter 5), Margaret was also worried if Milly baked while she was there, that the flour dust in the air would cause her to have a reaction. Margaret was in a dilemma. She didn’t want to request that Milly didn’t bake her favorite Christmas cookies, cakes, pies, and breads. In Milly’s mind, it wouldn’t be Christmas without them. And Margaret didn’t want to impose her dietary restrictions on everyone. Because Margaret is so sensitive to gluten, part of her transformation was to decide not to eat foods anyone else prepared. The only exceptions are if she co-prepares, or if the person making food for her also has celiac disease and is strictly gluten-free. On previous visits to Milly’s house, before Margaret’s transformation, Margaret ate “gluten-free” foods that Milly prepared, only to become sickened. When Margaret asked about ingredients, Milly said, “Oh come on… you are being so dramatic.” Margaret actually wondered if Milly didn’t “accidentally” slip gluten into her food just to observe what happened. Needless to say, they don’t have a trusting, loving relationship. Margaret determined the only way to stay safe is to bring her own food, cooking utensils for meal preparation, and an emetic, just in case she inadvertently consumes gluten. “Best to get rid of it fast than let it go through the body,” she said. Rather than worrying as she would have in the past, about bread crumbs on the counter, flour dust in the air, or being contaminated from the sponge in the sink, Margaret took the initiative to call her mother-in-law to ask: “How can we work together to accommodate my special needs during our Christmas visit?”

Asking the question this way suggests a cooperative attitude, and empowers Margaret to (re)broach the topic rather than sweeping it under the rug. It brings to light that Margaret has a bona fide disability that needs to be addressed. Margaret came up with a few ideas that she thought would protect her while visiting. During the conversation, Margaret explained that on way to her mother-in-law’s house from the airport, she would need to stop at a grocery store. She told Milly that she would need a designated cooking area in the kitchen that was hers, about 2” x 3” that she could put her things on and cover with a dish towel. She asked that all baking be finished 24 hours before she arrived (it takes 24 hours for the flour dust to settle). She asked Milly to have space in the refrigerator for her food (about the size of two gallons of milk) where she could put her bag of groceries – that everyone else knew to leave alone.

In the kitchen when cooking occurred, Margaret explained to Milly that she would need a burner so she could use the pan and lid she would bring with her to cook a one-pan meal. Margaret worked out how to make a quick, easy one-pan dinner and practiced making them at home so she could time her meal to be done when everyone else’s dinner was ready to serve. Her plan entails making a piece of fish or chicken she cooks half way (about 10 minutes), then adding slices of baked sweet potato, a fresh vegetable such as broccoli, and a little water for steam, then put the lid on it and cook it on medium for 10 more minutes. Margaret said since her pan is covered during the cooking process, if someone is cooking gluten containing foods, she won’t worry too much about cross-contamination. She plans to bring her own seasonings (since some packaged mixtures contain gluten).

Broaching that conversation with Milly shows a lot of courage on Margaret’s part – she owns her special needs. She is not imposing them on anyone, except to ask for room in the kitchen to be accommodated. She also commands respect and took the initiative to get it. She also took the burden of providing gluten-free foods from Milly – taking all of the initiative to purchase and prepare her own foods. As a hostess, Milly must be relieved, (at least you’d hope so.)

While driving from the airport to Milly’s home, Milly pushed back. Milly said she had plenty of frozen meats and vegetables in the house that Margaret could eat and that they didn’t need to stop at the store. Milly explained that she has a list, it wouldn’t take long, and then she’d be sure to have everything she needed. Milly said, “I’m insulted!” Margaret said, “Please don’t be insulted. I react to the smallest amount of gluten and this is what it takes for me to be safe. I really need you to understand I’m not insulting your food, you make beautiful foods I wish I could eat, but this disease makes it challenging for me. I’m doing what I need to do in order to stay well.” Under her breath, Milly said, “No wonder John has gotten so skinny!” Reluctantly, she agreed to stop at the grocery store. Then Milly said she wanted to make her special Christmas morning braided cinnamon roll to serve hot from the oven for breakfast. Margaret didn’t want to impede on any of the established traditions, so as a concession she said she would wear a mask while the roll was baking, but asked that Milly make the dough 24 hours prior to her arrival. John and Margaret adjusted their arrival date accordingly.

It is hard to demand that special needs are addressed, especially when staying in someone else’s home. Usually there is a “ruler of the kitchen.” Cooks tend to be territorial about their domain and don’t want people in their drawers and cabinets either. If you know there is someone in the home that feels this way, it’s best to have your own station somewhere off from the main part of the kitchen, so most of your food preparation can be away from where the “ruler” presides. In this situation, cooking on the same stove top is a problem. If you can bring a hot plate, that problem is resolved.

It takes courage to assert yourself in this way. If you already have strife in the relationship, this can easily add fuel to the fire – but it’s better to take precautions than to starve yourself, or be “glutened.” Some people, like Margaret react to such a little amount of gluten that it’s not worth taking any chances. I admire her courage and hold her up as a role model for how to gracefully travel and stay in someone’s home. She has inspired me to adapt her practices when I visit other people’s homes, though staying in a hotel where you can pre-make your meals for the day is so much less complicated (and peaceful).

It’s A Process

It seems that the first year or so, people often struggle to figure out what they can and cannot eat. They are coming to terms with their personal levels of sensitivity, which often change as the body gets cleaner. Several participants noted (and I have also experienced this) that the cleaner the body is (after avoiding gluten for a period of time), the more sensitive to gluten it becomes. Much of the first year is also spent in teaching our friends and loved ones the severity of the disease. It is hard enough for the person with celiac disease who has been consuming a lifetime of gluten to come to terms with a gluten-free lifestyle. As we have seen, study respondents described lots of struggles at home in the transition to gluten-free. Since food is integral to most social situations, many described relationship problems, breakups, separation, and general turmoil. Gluten-free restrictions permeate nearly every aspect of life. How families handle these restrictions is a barometer for how well they handle conflict and disruptions, often revealing other relationship problems. And over time, these food-related alterations might take a toll on all aspects of family life (Konrad, 2010) as we have seen with several of the participants who reported major changes in their relationships. There were problems before they were diagnosed; afterward, things escalated, so that the gluten-free diet became the catalyst that prompted change.

Grace (#17) conveys the heartbreak that accompanied her Big Shift (Chapter 6) and identity transformation:

I miss looking forward to eating. Sometimes I view food more as an enemy. I used to love it. I think back to the days when I would get excited about knowing we would go to a certain restaurant to eat. Or, when my mom was making lasagna for a special occasion. My family celebrated around food. When you look at photo albums of my family, there are more pictures of food than there are pictures of people. Because that’s what an Italian family does. And the holidays, the special things that were baked for a specific holiday, whether it was special Easter bread at Easter time or a certain Italian cookie for Christmas, or whatever the tradition was. I miss that. And I don’t feel that anymore because I can’t eat lasagna. Christmas comes and goes, and my mom makes at least 10 different kinds of cookies, and multiple dozens of each one. She starts on Thanksgiving, and she would put them in the freezer. She would put them in shoeboxes. And she would freeze them. And then at Christmas, we would have them. It’s been four years, and I haven’t had any. And she still does it. So I’m like, don’t even show me mom. She’s another one that doesn’t get it. She’ll call me and tell me, ‘Oh, yes, this morning I tried a new recipe for this homemade muffin’… And I’m like, ‘Oh, mom, really? Do I need to hear this? Do I need to hear about your homemade muffins?’ So, now I look at food more like an enemy. I get angry at it. I miss that excitement.

Grace’s story emanates remorse and a longing to enjoy her mother’s food with other family members. She also expresses anger at her mom’s lack of understanding of her dietary restrictions, and at her own inability to eat foods the way she used to. Food, which once represented practices of love, is now an adversary, and an enemy. Her homeostatic shift encompasses her grief, losing the ability to eat the foods of her heritage, as well as the acceptance that this is how it is from now on. She concludes the story with, “This is my reality.” Though she admits to mourning her past lifestyle, she conveys a high degree of acceptance and a transformed identity. These redemption stories illustrate how the sharing of our stories can result in rewarding transformations after the homeostatic shift. I also observed that people’s acceptance of life with celiac disease changed over time. The longer someone lives with it, the more they seem to adapt to the lifestyle. Those newly diagnosed seem to struggle more with all of the elements of what to eat and how to navigate the imposing cultural constraints. Those who have had it a while figured out what diet works best for their bodies, and have incorporated successful adaptive strategies for social encounters.

Throughout this book, we’ve learned that when we have a life-altering diagnosis, (or really any life-altering event), dominant cultural constraints may no longer serve us. We have to redefine our own set of “truths,” work with them to tweak them out for ourselves, such as when we experiment with foods and in social settings. It is a balancing act that takes time. In the past chapters, we’ve discussed examples of how respondents shared the discomfort of shifting truths in various venues as they struggled in the limbo stage: workplaces, restaurants, and schools. Here, cultural constraints were challenged and “truths” were redefined as a result of being diagnosed with an illness. Next, people experienced the Big Shift as they accept their new circumstances and attempt to gracefully navigate life in light of it. The Big Shift occurs when we realize life will forever be altered to a new definition of homeostasis. Finally, we transform our very identity to accommodate our new “self.” It’s a process that takes years. It certainly did for me.

Jean’s Transformation Story

Celiac disease has transformed nearly every aspect of my life, my occupation, and my social interactions. My individual transformation, as with most people, happens over the course of several years. Before I am properly diagnosed, I find myself between jobs. Feeling miserable and wondering who would hire me with my maladies, I decide to attend a vegan “healing” cooking school for a year. It makes sense to take some time off to regain my health. Diet is something I can control, and I hope it is the answer since none of the drugs doctors prescribe work. I find a cooking school that advertises teaching “The Art of Healthful Cooking.” It is a professional, certified school run by a culinary artist in Boulder, CO. I love it the minute I walk in. The aroma from the kitchen melds a combination of cumin, cinnamon, chocolate, green tea, chili powder, and lemongrass. It is intoxicating. The teacher teaches us the “Zen” of cooking, where the body and senses reflect taste combinations to the chef. Students never use a recipe and learn to creatively employ what is on hand. In the course of becoming a vegan chef, I learn about healing foods, grains, beans, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and fruits.

Other teachers at the school teach me how to make beautiful gluten-filled baked goods and how to manipulate dough to get the best crumb and texture. The most important thing I learn is “ratio” baking and the concept of “to fit.” Though the cooking school is not gluten-free, these techniques later enable me to develop recipes for my gluten-free baking cookbook. Another significant thing the teachers teach me is to focus on how the foods make you feel as it progresses through the digestive process. Does it make you feel satisfied and comfortable? Or, do you feel like your body is fighting the food? I don’t put two and two together, but it is a glimmer of what is to come. How I love that cooking-school phase of life! This experience contributes to my new identity once I learn my maladies are caused from gluten.

Shortly after I finish the cooking school, I am diagnosed with celiac disease. While I am glad to have a diagnosis, I still feel untethered. One day, my husband shows me an article in a magazine announcing a contest called “Win Your Dream Job.” It promises coaching from experts, a new computer system, cash, and best of all, the opportunity to consult with renowned career mentors appropriate to the winner’s dream job field. I fill out the entry form and send it in. And wait…

Wow, imagine winning! But even if I don’t win, just writing about my “dream” help me to formulate what my next step in life will be. Alternative Cook, LLC is born. I immediately start working on the first instructional DVD. I don’t know what gave me the idea that I would be as engaging as Rachael Ray, but when I watch the first few segments of the “takes,” I am embarrassed to see that I am a chatty airhead. One of the people who sees me in those early “takes” says I am condescending and bossy. (Now that hurt… and how can a person be bossy on a cooking video?) I am going for “warm, engaging, and insightful. Another describes me as “pleasant and straightforward.” That is better but I have a long way to go. Then one day, the phone rings. I am one of three contest winners! I feel validated.

Like others I interviewed, my life was transformed with the diagnosis. The process of attending cooking school, creating the instructional DVDs, becoming a published gluten-free cookbook author, and then realizing that gluten sensitivities impose social constraints and earning a PhD to study that, is how I came to terms with having celiac disease. Food has defined my life and it has been either my greatest nemesis or my healing solace, depending on my choices. It has determined how I spend most of my time, altered my career, and has consumed my thoughts for the last two decades. As I look back on this path, the steps I’ve had to take to surmount physical issues amaze me. It has truly shaped my identity, occupation, and trajectory for the second half of life, and I feel like I’ve been through hell and back with pain, suffering and dealing with some of the professionals in the medical community. As wonderful Julia Child said when her cookbook was initially rejected, “At least it kept me occupied for many years.” Celiac disease has given my life a meaningful purpose while evolving into my transformed identity as “an insecure, overachieving orthorexic.” I am grateful for finally being diagnosed, and for the life path it put me on.

Summary of the Transformation Process

We’ve now covered the components of transformation. Re-capping the Disease Process from Chapter 6: we live in our happy state of homeostasis until we experience a life altering event such as a diagnosis with celiac disease; then we question everything we once held as true, learning it isn’t true for us anymore; we enter the “limbo” stage or liminality where we have to experiment with new strategies in order to survive physically and socially. This is an uncomfortable stage when we think we’ve got it all figured out and the rug is repeatedly pulled out from underneath us. Slowly, we come to terms with it and enter into a new state of homeostasis where our new “truths” seem to be working for us. This is the Big Shift. Finally, we transform our lives so that living with the disease isn’t the focus of everything we do. It becomes normalized and we can function smoothly once again in life.

While undergoing the process of transformation, we have learned to command respect, to educate those we love, and to expect compassion. It’s a process that applies to anything that changes the way we think. Transformation doesn’t require a disease diagnosis to occur. It happened to the entire world when it was determined that the Earth wasn’t flat. Everything about how we had previously thought about the Earth changed in that moment. The collective population had to go through a process of transformation to re-think everything that had been previously thought. It happens when there is a global pandemic and we have to alter every aspect of our lifestyle, or when any life-altering event happens. This is the process we go through. Some get stuck in one component. For example, some may never get out of the limbo stage, as illustrated with the participant stories above. Others may never even get to the point of defining new “truths” because it is just so different from how they believed. For example, a religious person who thought of bread as a sacred food may never be able to eliminate it from their diet. By understanding the process, we can navigate ourselves through it, and hopefully get to the other side with a rewarding transformation.

Moving Forward

Having language equips us with tools to discuss these evolving “truths.” The next chapter provides a summary of the language developed herein, as well as proposing a catch phrase to efficiently communicate without long explanations.

Discussion Questions:

1. Describe what life looks like for you, now that you’ve completed the stages and entered into transformation.

___

References in Chapter 7

- Bacigalupe, G., & Plocha, A. (2015). Celiac is a social disease: Family challenges and strategies. Families Systems & Health, 33(1), 46-54. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000099

- Charland, M. (1987). Constitutive rhetoric: The case of the people Quebecois. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 73, 133-151. doi: 10.1080/00335638709383799

- Konrad, W. (2010). Food allergies take a toll on families and finances. New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast) May 15, 2010.

- McAdams, D. P., & McLean, K. C. (2013). Narrative identity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(3), 233-238. doi: 10.1177/0963721413475622

Continue to: Gluten-Centric Culture: Chapter 8 - Empowering Language

Back to: Gluten-Centric Culture: Chapter 6 - From Shaky Ground to the Big Shift

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now