Celiac.com 03/05/2021 - In 2003, I was on a business trip in New Hampshire when my skin blossomed into an itchy, burning rash. During the daylong meeting, I felt it spreading under my clothes. I delivered a presentation to 20 people, while wondering what was happening to me. After the presentation, I went to the bathroom and open my blouse. One look at my reflection in the mirror, and I fainted.

At the emergency room, I was confronted with seven different doctors, one at a time, who ask me if I have taken illicit or pharmaceutical drugs, or been exposed to fertilizer or dioxin. They told me that I was having a systemic chemical reaction. They prescribed steroids and antihistamines. They said the rash exposes my body to bacteria and instructed me to buy a thick sweat suit to wear on the plane ride home. The rash itched unbearably for ten days and took six weeks to heal. This was the first of many full-body rashes that erupted unexpectedly over the next few years.

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

Back home, I searched Google, study journal articles. I visited specialists who did colonoscopies, endoscopies, barium enemas, and x-rays. They prescribed histamine blockers and antihistamines. I went to dermatologists who performed skin-prick allergy tests and biopsies, prescribed more drugs and steroid creams. None of the doctors could diagnose the cause of the rash. Meanwhile, the shame around my rash caused me to become antisocial. I hid at home, mostly, but when I did venture out, I wore long sleeves, pants, and gloves to hide my skin even in the heat of summer. My hands were the worst. They swelled with inflammation and itchy sores. One summer afternoon on the light rail, I was too hot to wear gloves. A woman sat across from me, took one look at my hands, and found another seat.

The intensity of the skin affliction is an extension of my childhood malaise. I grew up with up with chronic stomachaches and bloating. I thought it was normal to feel sick after eating. Tests revealed that my intestines were anatomically correct albeit twisted, and I was told again and again there is “nothing wrong” with me. I ate a healthy and wholesome diet, following the nutritional advice of the day. Plus, restrictive diets were part of my family’s culture. My mother was always counting calories or on a diet, and after my father had a heart attack, the whole family followed his restrictive heart-healthy regimen.

After suffering a series of painful and humiliating rash cycles between 2003 and 2005, my husband found a doctor who promised to find the cause. I endured more scopes down the esophagus and up the rectum orifice, ninety-eight needle sticks on my back, and twenty-six bubble-tests on my forearms. Still, no diagnosis. Finally, after a lifetime of stomach issues, years of painful rashes, and three months of exhaustive testing, the doctor concluded that I was reacting to gluten. My symptoms were conducive to “a rare form of celiac disease called dermatitis herpetiformis,” he said.

The first rule of war according to Sun Tzu: “Know your enemy.” Learning that a protein called gluten was wreaking havoc on my body, I was determined to fight it with dietary changes. Gluten wasn’t part of the lexicon at the time and the so-called “gluten craze” was years away. I was left to research on my own. On the Internet, I read, “gluten is a protein found in barley, rye, oats, wheat, and spelt.” Think of the acronym BROWS. But that is just where gluten ubiquity begins. I learned the scores of synonyms for gluten, so I could parse labels on foods, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. I discovered that virtually every food I consumed contains hidden gluten. Even with this knowledge, I’d be rash-free for a while, only to have another devastating surprise outbreak. This lasted several years after diagnosis, in spite of vigilantly controlling my diet.

Over the years, the rashes have become fewer, as I learned the constraints of my condition. If someone had told me how vigilant I’d have to become, I would have said, “Are you kidding me?” Every bite of food I don’t carefully scrutinize puts me at risk; even the tiniest infraction causes a reaction. I have zero resistance. Explaining my food idiosyncrasies to others is a challenge. My family members support me, though I’ve been accused of “trying to get attention,” and my childhood stomach issues have never been fully acknowledged. I trust almost no one to cook for me. Too many times I have believed loved ones who said that a food is “Jean friendly,” only to be sickened and suffer another rash-cycle. Social politeness isn’t worth the damaging physical ramifications. Food is subsistence for me, now. I limit my diet to the few foods I know will not make me sick. With these strategies, I have learned how to live and thrive with celiac disease, but it has been a long and painful journey, because not eating gluten subjugates me from many social situations.

A Social Disease

After living with the disease for over ten years, speaking around the country and talking to folks with it too, I realized that the important thing about having celiac disease isn’t answering the ever-important question “what’s for dinner,” but rather, how do I gracefully navigate social scenarios with people I love without alienating them, or compromising my health? I realize that celiac disease and food sensitivities are a social disease (Bacigalupee & Plocha, 2015). We live in a world that revolves around eating gluten-containing foods such as cake to celebrate an achievement, Holy Communion to unite with Christ, or breaking bread at a meal to signify friendships. Those that cannot eat gluten are cut off from these rituals, causing feelings of isolation and seclusion. Constant ridicule of gluten and gluten-avoiders in the media only add to these feelings of alienation. To understand how this affects people in their familial and friend relationships, I surveyed over 600 people and interviewed nearly 70 people nationwide who live with celiac disease or other food sensitivities, asking them to convey their recollected stories.

Contentious and sometimes compassionate social interactions take place in what I am calling “vexing venues” such as the home and dinner table, holiday and extended family meals, church, restaurants, the doctor’s office, school, and even the bedroom. Since food appears in virtually every social encounter in life, those with food sensitivities or celiac disease find themselves confronting social norms every day. The attitude of those around us, coupled with our fortitude and self-confidence, or lack thereof affects how we manage these social situations. Sometimes things go well, and we can avoid confrontation and blend into a situation; other times, we are left without anything safe to eat, and people around us who simply do not understand. Positive and negative interactions described by study participants instill a need for a work such as this one to create new levels of awareness, and to be a catalyst for change in the way gluten-centric rituals are viewed. This happens on the individual level first. As described in “The Diagnosis,” and as reported by so many of my study participants, the process required to figure out what is safe to consume is scary, especially when we may react severely to even the smallest amount. But after we figure that out, we have to decide how best to communicate our needs, and live with them in everyday life. It ain’t easy!

“None of us are going to follow that diet!”

I recently met a woman in the pet shop as I scanned the shelves for gluten free options for my two kitties. The woman noticed I was reading the labels and asked me what I was looking for. I said, “Gluten free cat food, if you can believe it! I can’t clean vomit from the kitties if it contains gluten, so I need to find alternatives.” She then asked me if I had celiac disease. I said, “yes” and she told me about her niece. Her niece had been diagnosed with celiac disease a year ago, but her family did not understand anything about it. The girl was afraid to eat anything, withering away and getting very thin. I asked her if the other family members continued to eat gluten in the household. The lady replied, “Well, yes, of course. None of us are going to follow that diet!” I said, “Does your niece react when she consumes it?” The lady said, “Well, she has lots of physical problems, and she is a very picky eater, but we don’t know what’s ‘in her head’ versus what is real.” Then she described how the family (and she) felt like the girl overreacted, so they forced her to go to a rehabilitation clinic where she was diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. She is now back home, and struggling. This poor girl needs help to understand what she can safely eat, but clearly her biggest issue is negotiating with her family to come to terms about how to keep herself safe while living in that household. The lady described a huge amount of resistance from the girl’s family members, and a lack of compassion or understanding. Until those attitudes are changed—both by the girl and her family—she will not thrive. Why are the family members acting this way toward the girl? It’s because they are entrenched in their beliefs, and the girl’s needs are so far from what they hold as “true,” they cannot comprehend her needs. Also, the family is using “groupthink,” where they reinforce each other’s opinions while inadvertently hurting the girl (Janis, 1972). Though celiac disease and anorexia are serious, ultimately, the family’s firmly held “truths” are the root of that girl’s problems.

Once diagnosed with a disease such as celiac disease (and being diagnosed is a feat in itself), the person goes through a process where they realize that long held “truths” about what they can or cannot eat, and how they participate in social situations is completely different than what it was before. Cultivating new “truths” takes time, experimentation, trials, and errors. It means trying out one social tactic or another to see how best to co-exist. It requires strength and courage by the person with celiac disease or food sensitivities, and ideally cooperation and compassion from family and friends. This process is necessary in order for the person with food sensitivities or celiac disease and their close loved ones to adjust. As medical diagnosis processes improve, gluten intolerance is known now to affect many.

Gluten Awareness

Roughly 95 million Americans—one in every three people—react negatively to gluten (Fine, 2003). Yet, “going gluten free” is considered a fad, ridiculed in contemporary culture, denigrated by culinary luminaries, and even refuted by the Pope! Since being diagnosed with celiac disease in 2005, I have been vaguely aware of the societal pressures that put me at odds with friends and family in virtually every social setting where I disclosed my intention to maintain a gluten-free diet. I wonder, why do I feel this way? Why was this happening so consistently in my life? And, was I alone in this experience?

Celiac disease affects one in every 100 people in the United States (celiac.org). Despite these high incidence rates, American physicians often erroneously perceive it as a rarity (Fasano et al., 2003). While three million Americans have celiac disease (Fasano, Sapone, Zevallos, & Schuppan, 2015), another three million have non-celiac gluten sensitivity, which is also an autoimmune response to gluten (Uhde, et al., 2016). And one-third of Americans likely have gluten sensitivities, defined as illness from eating gluten that is not detected in current serological tests (Fasano, et al., 2015; Fine, 2003). The lack of diagnostic testing and awareness leaves many others with non-celiac gluten sensitivity and food sensitivities unaware of the correlation between their symptoms and consumption of gluten-containing foods (Wangen, 2009). Most adults are diagnosed at age fifty or older (Goddard & Gillett, 2006), and non-diagnosis of celiac disease can result in lymphoma (Green & Jabri, 2003). Non-celiac gluten sensitivity affects at least the same amount of people as celiac disease but there are no medical markers to confirm diagnosis at present; however, other autoimmune indicators are positive with the consumption of gluten in tests (Uhde et al., 2016), suggesting that celiac disease is not the only disease correlated with gluten. Pharmaceuticals exist to address symptoms of intestinal discomfort and other physical manifestations, but there is no medical cure for celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity (though hope on the horizon is discussed in chapter ten). Those with DH can take the drug Dapsone to alleviate the symptoms, but it has serious side effects. Currently, the only treatment option for those with celiac disease is a strict gluten-free diet for life (Fasano & Catssi, 2012).

Symptoms of celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity affect the intestine, including “gas, bloating, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fat in the stool, nutrient mal-absorption, and constipation” (Fine, 2003, p. 1), and may manifest as autoimmune issues affecting the entire body, including “dermatitis herpetiformis (itchy rash), diabetes, chronic liver disease, multiple sclerosis, lupus, and osteoporosis” (Fine, 2003, p. 8). Most people don’t correlate what they eat with these physical responses, and reach for an antacid rather than adjusting their diet. Americans spend over two billion dollars a year on antacids (Statista, 2016) when simple alterations in the diet may alleviate symptoms. Some people with celiac disease are asymptomatic. They are the lucky ones who can go to a restaurant and order the featured gluten-free meal and won’t know whether the food was cross-contaminated because they don’t react. This is risky too, because they may be building up antibodies and not know it, and to be honest, their ability to take risks makes those who can’t take risks look overly cautious. Despite it’s commonness, most people don’t know much about gluten sensitivity. Nevertheless, being diagnosed with celiac disease or food sensitivities means having to rethink everything – how we eat, what we eat, where we eat, whom we eat with, and how at-risk we really are. We have to learn for ourselves whether we are asymptomatic, or highly symptomatic. It’s a process of relearning and unlearning, as we navigate our new “truths.”

A Rift with Truth

Changing a “truth” often creates dissonance for everyone involved. I find it fascinating to associate how deeply held “truths” affect relationships, and when these “truths” are disrupted (such as with a diagnosis that disallows a food found in virtually every bite of “normal fare”) relationships are impacted. What causes this rift with constantly held truths? What factors cause us to form these “given truths?” To answer this, it makes sense to start with defining ideology. Ideology is the kind of word that if you asked nine people what it means, you’ll get nine different answers. (Incidentally, I’ve done this!) Ideologies are common-sense taken-for-granted expressions that influence what is considered “truth” in a given community. There it is – the simple explanation of what “ideology” is—a taken-for-granted truth. Each ideology is informed by a system of ideas that support prevailing social practices and beliefs that are considered natural or normal. However, what is natural and normal for one set of people may not be for others. Consider the global warming controversy. Some consider it “true” that there is no global warming, while others consider it “true” that there is global warming. Those are two ideologies that come with a whole set of sub-beliefs. Convincing someone to change their “given truths” is challenging, and requires compelling evidence. And there is another aspect of ideology – we may know there is global warming, but decide to ignore it, treating it with willful ignorance, because as Al Gore points out, it is a very inconvenient truth. It is no fun to alter our fast-paced, technologically driven lifestyles to accommodate the planet’s needs. It is easier to rationalize making a larger carbon footprint when we have the chance to travel across the world for a tropical vacation, or drive rather than use public transportation. Similarly, it is complex to alter a person’s diet to completely omit gluten. It is far easier to conform to norms than to insist on eating different foods than everyone else eats.

Ideologies are determined by cultural influences such as religious beliefs, etiquette practices, media perspectives, political views, “scientific” evidence (put in quotes, because outcomes can be manipulated for biases), and the cultivation of “truth” through storytelling. Storytelling is how we determine who we are, and what we believe. Our “story” is influenced by our experiences, what we see, read, hear, etc. as well as what those around us see, read, and believe. Collectively, we form what we consider “truths” or ideologies. For the purpose of this book, “given truths” and “ideology” are the same, but they vary from person to person, and culture to culture. We live with our taken for granted “truths” very comfortably, thank you very much, until they are rocked with a new “truth” that has to be evaluated and incorporated. A perfect example of this is when a person is diagnosed with celiac disease and has to avoid every molecule of gluten in order to thrive in life. Everyone else has to alter his or her “truths” to accommodate this new “truth.” Often people don’t want to alter their comfortable “truth,” causing resistance. Sometimes the notion of a severely restrictive diet is so farfetched, people “refuse to believe it” causing head butting and strife.

I recently “butted” against an ideology with my housekeeper, who had been with me for years. I thought she understood my gluten sensitivities, because she has been in my life as I wrote cookbooks and renovated my house to make it safe and gluten free. One day she arrived at my door munching from a cylinder of crackers. I said, “Oh, I’m sorry, but you can’t eat those in here. Before you come in, you’ll need to wash your hands. Please wait there and I’ll get you a damp towel.” All ended well, it seemed. But then months later, I found her eating chocolate chip cookies in my gluten-free kitchen. I said, more forcefully, “You can’t eat those in here! Please put those in this plastic bag, and let’s try to clean off whatever you have touched.” To my surprise she responded, “You have insulted my food again! You did it before when I was eating crackers. I’m hungry and need to eat. I’ll eat whatever I want whenever I want to.” When this happened, I didn’t say to myself, “Oh we are operating from different ideologies.” Nope, after she rejected the gluten-free food I offered instead of her cookies, I just got really mad and fired her. In fact, I fumed about it when I had to clean up (and had a reaction as a result). I still fume every week when I clean my house myself now.

But when I think about it, I realize that she was operating from a different set of “truths.” Her “truth” was that she was working hard and was entitled to eat when she was hungry. The idea of a food allergy or intolerance was alien to her. Somehow she missed noticing the years I was sick when she came to clean before I was diagnosed, or the other years I worked from home writing cookbooks. Though I thought I had explained it to her many times, I think the idea of being “allergic” to any food was a concept she simply didn’t understand. From my ideological perspective, after forsaking nearly every food I used to dearly love, eating an extremely restrictive diet, and living this lifestyle, I was absolutely confronted with her attitude and lack of respect or compassion for my plight. We were operating from two polarized ideologies. I am sure she felt as “right” with her beliefs as I did with mine. Both of us were reinforced by prevailing “truths” we elected to hold as our own.

Members of the dominant group reinforce their own values and tend not to question their ideological beliefs. When individuals outside of the dominant group question the ideology, they are often subjected to scrutiny, judgment, and disciplining tactics, as the dominant group seeks to protect existing ideology. Major life changes, like illness, can displace a person’s position from the dominant group to an outsider group. For example, when given news of a life-altering illness requiring drastic dietary alterations, a person may reexamine firmly held truths around food and health. Ideological truths that once represented simple proclamations to live by (such as give us each day our daily bread, for example), suddenly contradict reality. The ill person reexamines his or her ideologies around social and familial situations involving food, forced to defend them with everyone else who holds a different set of beliefs.

The Power of Ideology

Expanding the simple definition of ideology as taken-for-granted truth, let’s examine it from different perspectives. An ideology is described as a notion that drives behavior, but that behavior can be altered when a different belief takes hold (Burke, 1969). My housekeeper’s reaction depicted her deep-seated ideological belief that she was entitled to eat whatever, wherever, and whenever she wanted, and that allergies to food were unthinkable. Whereas, I felt like after all I had gone through to learn about my disease, and the sacrifices and expenses that I had endured to thrive, she was disrespecting and disrupting my ideologies (in the sacredness of my home). There was no intersection between what she believed and what I held fast. Unified, or common beliefs would have helped us to understand each other’s perspective. My housekeeper and I shared no “interconnected beliefs” on this topic (Black, 1970, p. 70) and because of that we reached a sudden impasse and parted ways. I truly regret this. She was with me for years. I wish we could have a heart-to-heart about this, where I could say my point of view and she could express hers. It would be wonderful for us to show each other compassion and understanding, but it hasn’t happened. She “dug in” with her truth, and I with mine.

Ideologies are seldom an individual’s original thought, but rather a thought driven by outside influencers (McLellan, 1986). Ideologies are common sense “truths” (McKerrow, 1989), and may be rooted in personal, self-serving interests (Eagleton, 1991). For example, a spouse who feels put upon by his/her partner’s gluten-free needs may repeat the ideological “truth,” a little won’t hurt you, in order to avoid the burden of extreme safety practices in the home kitchen. Operating under this ideology, the cook is excused from the tedium of reading every label to identify gluten-containing ingredients. The partner eating the food becomes a victim of this ideology when suffering the consequential reaction. I have a friend who continues to make gluten-containing foods in her kitchen even though her husband constantly complains of what she refers to as “his little rash.” He was diagnosed with dermatitis herpetiformus, a form of celiac disease that manifests on the skin a few years ago, but she refuses to believe he is as intolerant as the doctor told him he was. She thinks a little won’t hurt, and even though he has that “little rash” all the time, she continues to bake and eat gluten. He is a victim of her ideology.

Faced with the challenges of a gluten-free lifestyle, some couples forego eating together. Study respondent, William (#60) describes his sadness that he and his wife no longer share meals. She doubts his response to his disease, judging his restrictive dietary choices are far too extreme. He reports, “She goes out to eat most of the time, and I make safe food for myself at home.” His wife refuses to cook or consume gluten-free meals, preferring to eat at restaurants with her friends. William feels isolated and distanced from his wife because of his extreme sensitivity to gluten, unable to participate in her social events. However, he remains steadfast with his resolve to avoid cross-contamination to protect his health.

Another respondent reports feeling mocked with his dietary choices. When eating his special gluten-free foods at the dinner table, Bert (#63) says, “My daughter rolls her eyes and looks at my wife. They both snicker.” The daughter and wife are showing reluctant tolerance and gluten-doubt ideologies to his dietary choices. These ideologies will be elaborated in Chapter 2. Both examples from William and Bert show how living under flawed ideologies can disrupt relationships.

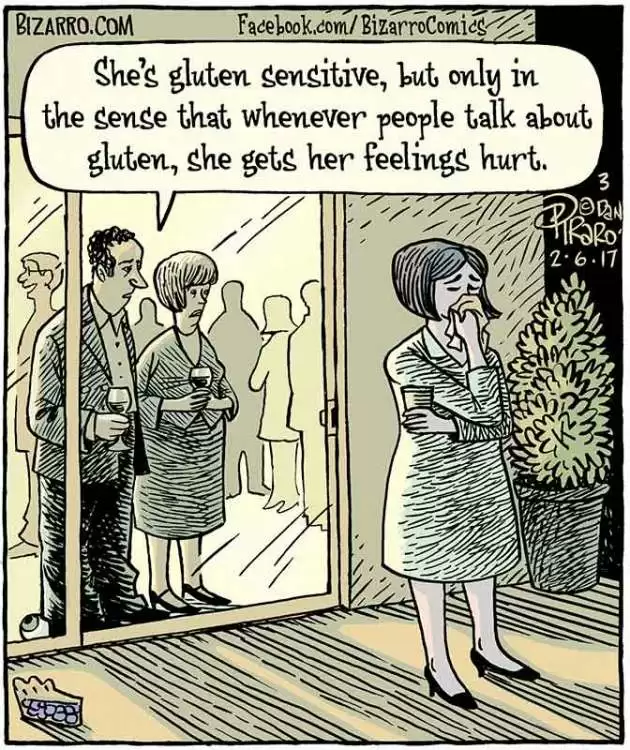

Ideologies are also enforced by the power of the elite class, including political, economic, and even military entities (McGee, 1980). The government perpetuates ideologies with dietary standards and corporations create physical ideals that sway the public through advertisements. Media influencers such as television shows targeting food sensitivities people, quotes from celebrities about the gluten-free diet, and mocking messages such as those the in satirical comics gathered in this text collectively influence the behaviors and ways of popular thinking. Utilizing the definition of ideology as a “shared representation of social groups,” ideologies evolve from cultural societal foundations such as the church, media outlets, weight-loss enterprises – from virtually every public venue (Van Dijk’s, 2006, p. 115). Stated differently, ideologies are mandates prescribed by a higher power such as religion, from an authority such as science, or from a powerful government or corporate entity. Ideology can comprise a constellation of beliefs that shape identities and realities (Mumby, 2015). Those whose actions repudiate established norms are punished, often with public ridicule.

Figure 1.1 – Gluten Sensitive (Licensed with permission from Comics Kingdom (Bizarro).)

Social commentary in the media often ridicules those who avoid gluten. Humor can be a harmful vehicle such as the comic in Figure 1.1. The woman is described to be overly sensitive, not to eating gluten, but having her feelings hurt when gluten is mentioned. Though admittedly funny, this is an example of how mockery can infiltrate the public’s opinion when someone request a safe, gluten-free meal, and how women are overly sensitive to diet. The satire comics presented throughout this book illustrate an ideological hostility to food sensitivities and celiac disease, by way of denigrating barbs that make light of the gluten-free diet, undermining the importance of it, and reinforcing negative and unkind behaviors toward those with celiac disease. Laughing at a gluten-mocking comic implies agreement with the underpinning ideology. Freud (1905, p. 60) points out that wit is a “weapon of attack” to make those being disparaged feel “inferior and powerless.” If we fall outside of the norm with our behavior or beliefs, we are often ridiculed until we fall back in line. The comics illustrate how mockery urges conformity. Those in the “powerful” (non-celiac disease) group see the comics and laugh, whereas even though those with food sensitivities or celiac disease find it humorous, we also may view it as a form of “oppression” and a worrisome jab. Comics reinforce the “groupthink” that happens in families causing anyone who falls out of line to become the ridiculed victim, ousted from the group.

Humans coalesce in groups with common beliefs. “Man is by nature a political animal with an innate tendency to form into groups” (Aristotle). Groupthink is a process described originally by Janis (1972) where those empowered in a group share a common belief, whether it is true or not, and then put pressure on those who do not comply with those truths. Those not going along with the group’s ways of thinking are censored, ignored, or ultimately culled unless they comply. Those who share the group’s opinion are unified members of the group. Groupthink evolves through the process of familial storytelling where “truths” are formed and solidified, sometimes becoming self-censored, and self-serving (Janis, 1972). Ideologies are assimilated through conversation that conveys a story that intertwines cultural influences with long-held beliefs (Fisher, 1989). Narrators balance truth with motivations in a cohesive story with significant meaning (White, 1980) and seek reinforcement or agreement from outside culture, religion, and political influential forces (McAdams, Reynolds, Lewis, Patten, & Bowman, 2011). This story telling process to formulate “truths” is integral to family traditions, making meaning of shared life, “doing family” (Langellier & Peterson, 2018, p. 1), and teaching family values (Koenig Kellas & Kranstuber Horstman, 2015). It is in our initial home where we learn fundamentals for what and how to eat, how to cook, how to participate in food-related rituals), as well as gender roles and power structure biases around food (de Certeau, et al., 1998; Pecchoni, Overton, & Thompson, 2008). Groupthink is a way of encouraging belonging to the group or family and creates power structures of “us” and “them.”

Divorcing the Family

Originally published as an excerpt from this book on 02/13/2020 in The Journal of Gluten Sensitivity

I made a rare visit to a cousin a year or so after I was diagnosed with celiac disease. As the youngest child in a large extended family, my cousin was closer to my mother’s age than mine. He took my mother and me on a beautiful ride around Kansas City. I sat in the back seat as they reminisced about their younger lives while passing the places where they experienced them. It came time for lunch and he wanted to take us to a favorite BBQ place in the heart of Independence, MO. I hesitated at his suggestion, and he said, “You aren’t one of those vegematerians, are you?” The coy word he used, and his tone suggested his disapproval of anything out of the ordinary. (In fact, at that time I was a gluten-free vegan!) I said, “I’ll find something.” During lunch, I picked at French fries, pretty sure they were cooked in a dedicated fryer. My mother and cousin exuberantly scarfed the BBQ. My cousin told us about another cousin I hadn’t seen in over 40 years that I apparently look like and reminded him of. He said, “Cousin Sandra is weird. She used to bring her own food to our family dinners.”

He was referring to a time, fifty years ago. Back then, members of the extended family met at my grandmother’s house every Sunday to share their views on politics and happenings in the world. It was a close-knit family. Dinner consisted of the main dish (usually pressure cooked ham, green beans, onions, potatoes, bread, and cake for dessert) made by my grandmother, and side dishes brought by my aunts. I was no older than five, and have hazy recollections of these dinners, other than the warmth of family and the familiar smells of home cooking. To be included meant to eat, drink, smoke (it seemed they all did it back then) and converse around that big dining room table. I can imagine that someone daring to bring their own food, spreading it out on their placemat and eating it, while all those other dishes were being passed, might not go over well.

As I reflect on my cousin Sandra, it occurs to me that she may have had celiac disease. That was in the early 1960s when it was virtually unheard of in the United States. Why else would she have had to bring her own food to those cherished dinners? A diagnosis prohibiting food of any kind would have been alien and unfathomable to anyone in my family. These are people who lived through the depression after all, where popcorn was the fare for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, if they even had that! Waving away any food, especially foods made by loving hands would have been viewed as an arrogant rejection of their abundance and love.

Perhaps she had a mental illness that made her “weird,” or maybe she made unreasonable demands on the family, but I think the most probable reason is that she was just trying to protect her health. Considering how my cousin put it, she was weird only because she brought her own food to the family dinners. In his eyes, she became the “weird one,” ousted by the family because of her audacity to bring her own food to the dinner party. Family lore according to my mother goes on to say that: “She ultimately divorced our family.” Can you do that?

It’s a sad story, isn’t it? But I think about it from time to time. I wondered if Sandra was so maligned because the family decided her special needs were so odd that they ostracized her, and she ultimately rejected them. Further, they unified at her expense. Does what happened to her mean that anyone in the younger generation who may have inherited the same disease runs the risk of being shunned? I’d like to think we’re more enlightened now, but thankfully, I’ll never know. I do recall that my mother shushed family when they talked about their illnesses around me, fearing I’d imitate them, I suppose. Her attitude was that you made yourself well, or you made yourself sick, and I think she was careful to protect me from hearing about other people’s illnesses so I didn’t get the idea that I may have them too. She had a Pollyannaish perspective, and thought everyone in her family was perfect, no matter what. That made it very challenging for me to convince her that something wasn’t perfect with me when I was finally diagnosed with celiac disease. In fact, I think she thought I brought it on myself. [I was in my mid-forties when properly diagnosed.] These were her “truths” and likely the “truths” of the collective family.

Most of those people around that dinner table fifty years ago have passed on, I imagine happily gathered “around that table in the sky.” In Sandra’s case, family members didn’t understand her dietary restrictions, agreeing she was “weird” and rejecting her for her special needs. She was stereotyped as a prima donna. Cumulative family lore develops through repeated acts of storytelling formulating familial ideologies that perpetuate collective “truths.” These stories form the group’s opinion on given topics. Sometimes these “truths” evolve from just participating in the same activities together, and developing a way of doing things that everyone agrees on, as described with the Sunday dinners above. In their lively discussions, my extended family debated “truths” about politics, news stories, and current events. Similarly, they had a collective opinion about how each other should act while sitting around that table. When someone altered the established norms, like Cousin Sandra, she disturbed rituals, and rocked the family’s agreed-upon “truths.” Her rejection of the foods required the family to rewrite their collective story. This is rarely done on a conscious level, but rather it is done as groupthink. The unspoken “truth” was: you do what we do, eat what we eat, and even smoke what we smoke in order to fit in. Buck that system, and suffer the consequences.

In Cousin Sandra’s case, the group determined her choices were a rejection of the others. She refuted the established but unspoken ideologies. As a result, she was rejected and mocked. From their view, if she didn’t participate, she self-selected alienation. Before rejecting her, they likely cajoled her to participate, suggesting a little won’t hurt you, or come on, just a bite. In fact, I can “see” my grandmother holding up a fork with a bite on it, saying, wouldn’t you like just a taste? These urgings are attempts to include rather than exclude. What they really are saying is: you don’t want to be rejected by the family by refusing our norms… come on, just have a little so you can stay a part of our group. That is actually a compassionate message. But we don’t “hear” it that way when we’ve deemed the food being offered to us as poison, and when we feel our needs are not being honored or understood.

I don’t think anyone in my family ever intended to bully Cousin Sandra out of the group, It just happened because of their rigid policies on how we ought to act perpetuating the ideology: Think like us, and belong. Sandra’s response could have been, “I love all of you, but not enough to eat your food.” I doubt anyone ever talked openly about it because they lacked the tools and skill to broach a constructive conversation.

Liza (#68) reflected on when she first sat down to her future mother-in-law’s table:

My fiancé and I traveled to my future in-law’s home so we could meet each other. I sat down to the dinner table. There were foods I was unfamiliar with – a whole fish cooked complete with the eyes, some pickles that smelled odd to me, some ultra sweet cakes, cold cuts, cheese, and boiled eggs. Though I was hungry, all of the foods were unappetizing to me. Really, I became nauseated and I knew that if I didn’t eat the foods my mother-in-law prepared for that first meal, she would feel that I was rejecting her. I forced myself to eat it, but still get chills when I think about that fish looking at me from the platter.

Liza conveyed that she wanted to make a good impression on her future parents-in-law, and she knew that not eating the food on the bountiful table was not acceptable. She wanted to fit in, but the food was unappetizing to her. She said that in the future she offered to bring a dish she liked to share at the family meals. Food is so integral to our social existence that forsaking the foods made by loving hands implies a repudiation of those hands, and the people who share it. Breaking bread around the dinner table is a way that people bond. Not taking that bread, or accepting that cup of tea, or eating what everyone else eats, is viewed as a silent form of rejection. This is why having gluten sensitivities causes so many social issues, and is one of the topics in my book. People I surveyed and interviewed told me many stories like the one above. As I reflected on what people said, I realized that the heart of the problem is that we do not have language to talk about these things. If we could say, “I’m not rejecting any of you by not sharing your food. I have a disease that prevents me from eating it, and I still want to sit at this table and be a part of the conversation.” We just don’t seem to be able to have these candid conversations. But by identifying these flawed social norms, we can work to change them, so people rejecting food served around the extended family dinner table can be included, loved, and un-judged for their choices. The first step is to identify these long held “truths,” put words to them, and discuss them openly, rather than living with unstated dysfunctional consensual rules that cause people who defy them to be alienated.

Ideologies in Culture

In this book, I explore how dominant beliefs drive behavior patterns of commensality (the act of socially sharing food). Ideologies are complex, with many activated at the same time around behavior, such as rules of etiquette, and acceptable religious practices. When on the powerful side of the ideology, life is natural and normal and social interactions are smooth. However, when on the oppressive end, a person can be subject to scrutiny or even punishment until they conform to expectations. This is particularly true of practices and beliefs surrounding food. Traditional foods and preparation practices are disrupted when dietary restrictions are expressed, deviating from expectations and requiring adjustments in beliefs as new narratives emerge (Bochner, et al., 1997). Food is often the focal point for ritual, ceremony, and everyday life.

When considering ideologies concerning food practices, it all comes down to expectations. These maxims drive behavior patterns and set social standards that govern acceptable social behavior, rituals for traditional ceremonies, and practices to assure health and welfare. Dogma related to gluten or gluten-containing foods is deeply coded in ideology such as you are what you eat and gluten-free is a fad. This means they are a system of ideas and principles that are taken as natural and normal, implemented without thought. These “truths” put individuals on the defense when communicating the severity of their food allergies or autoimmune reactions, because they simply don’t serve us anymore. Ideologies diminish the seriousness of food sensitivities in nearly every social setting.

Ideological Conundrums

Therein lies the rub. People who are diagnosed with celiac disease or gluten sensitivities are faced with the need to redefine “truth,” as they learn about the extent of their sensitivities and reactions to various foods. These new “truths” must be teased out and tested by the individual with celiac disease or food sensitivities until firmly believed, and then communicated and hopefully accepted by his or her peers. Cousin Sandra’s attempt and reaction illustrates how this testing can play out, for better or worse. Participants in the interviews discussed this book share their experiences while trying out new “truths” in various venues. Many shared that it was a tricky proposition, requiring them to learn more about themselves, how they handle conflict, and how they co-exist with loved ones. If a person is diagnosed with diabetes, they face having to make diet and lifestyle changes, but they don’t get mocked and ridiculed by society. People with diabetes are often treated with more compassion and understanding. Similar to celiac disease, diabetes is a genetic disability that requires constant dietary vigilance and daily management. An Internet search on “diabetes fad” versus “gluten fad” reveals that diabetes is not considered a fad and is taken significantly more seriously than celiac disease. Whereas the Internet search on “gluten fad” yielded multiple pages of hits. Perhaps diabetes is not considered a fad because doctors regularly test for it as part of an annual check-up, and because approximately 22 million Americans have it (Statistica 2016b), compared to only one million people diagnosed with celiac disease (Fasano, et al., 2003). Those avoiding gluten face cultural, gluten-centric forces that make “being gluten free” very challenging. As truth is redefined, the individual with celiac disease or food sensitivities undergoes an identity transformation.

The book examines three themes: ideological drivers related to food and gluten, familial adaptations or non-adaptive responses, and identity transformation with disease. First, we’ll uncover what causes ideologies to form by examining governmental regulations, religious beliefs, etiquette practices, media, and advertising to see how they define our gluten centric society. Next we’ll look at how ideologies affect family and friend social interactions. One chapter attempts to “rewrite” the script with our newly acquired knowledge of dysfunctional ideologies. We’ll check in with individuals from the study to learn how they handle these newly adapted “truths” and how they shifted their thought process to positively transform their lives. Finally, I’ll share the wealth of information gleaned from the interviews, discuss the American Disabilities Act (ADA), and end with “where do we go from here.”

In future chapters, I’ll explain the notion of ideologies in more detail, but for now, please understand that this “shift” in thinking redefining long-established “truths” is a fundamental transition for individuals determined to remain gluten-free. The next chapters define and discuss ideological influencers which I term: reluctant tolerance, gluten-doubt, able-body bias, “sorta scientific,” I-Know-Best, diet discretion, exclusionary etiquette, absence of agency, sacred bread, dietary discretion, sexist scrutiny, size surveillance, living by the numbers, and yours, not mine as they relate to food and gluten referring to taken-for-granted “truths” that inform guide daily life when interacting in rituals with others. These ideologies stand between living with celiac disease with grace versus living with strife and angst. Identifying them and offering language to define them is the first step to navigating the gluten-free lifestyle gracefully.

Discussion Questions for Forum

- How do your “truths” about gluten sensitivity differ from the “truths” of your family and friends?

- How do those differences in “truth” affect your social encounters with your family and friends?

- How do you convince your family and friends about your newly discovered “truths” as you navigate the gluten-free lifestyle?

Copyright © 2021 by Alternative Cook, LLC

Continue To: Gluten-Centric Culture: The Commensality Conundrum - Chapter 2 - Ideologies In Our Gluten-Centric Society

___

References in Chapter 1

- Bacigalupe, G., & Plocha, A. (2015). Celiac is a social disease: Family challenges and strategies. Families Systems & Health, 33(1), 46-54. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000099

- Black, E. (1970). The second persona. In C. R. Burchardt (Ed.), Readings in Rhetorical Criticism (pp. 70-77). State College, PA: Strata Publishing, Inc.

- Bochner, A. P., Ellis, C., & Tillmann-Healy, L. M. (1997). Relationships as stories. In S. W. Duck (Ed.), Handbook of Personal Relationships: Theory, research, and Interventions (2nd ed., pp. 307–324). Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons.

- Brown, B. (2013). Brené Brown’s presentation caught Oprah’s attention. The same skills can work for you. Retrieved July 23, 2018 from https://www.forbes.com/sites/carminegallo/2013/10/11/brene-browns-presentation-caught-oprahs-attention-the-same-skills-can-work-for-you/#604ac79053c1

- Burke, K. (1969). Rhetoric of motives. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- de Certeau, M., Giard, L., & Mayol, P. (1998). The practice of everyday life, Vol. 2. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Eagleton, T. (1991). Ideology: An introduction. London, England: Verso.

- Fasano, A., & Catassi, C. (2012). Celiac disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 267(25), 2419-2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1113994

- Fasano, A., Berti, I., Gerarduzzi, T., Not, T., Colletti, R., Drago, S., Elitsur, Y., Green, P., Guandalini. S., Hill, I., Pietzak, M., Ventura, A., Thorpe, M., Kryszak, D., Fornaroli, F., Wasserman, S., Murray, J., & Horvath, M. (2003). Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States. Arch Intern Med, 163, 286-292. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.286

- Fasano, A., Sapone, A., Zevallos, V., & Schuppan, D. (2015). Nonceliac gluten and wheat sensitivity. Gastroenterology, 148, 1195-1204. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12049

- Fine, K. (2003). Early diagnosis of gluten sensitivity: Before the villi are gone. Transcript of talk given to the Greater Louisville Celiac Sprue Support Group. Retrieved November 10, 2018 from https://www.enterolab.com/StaticPages/EarlyDiagnosis.aspx

- Fisher, W. R. (1989). Human communication as narration: toward a philosophy of reason, value, and action. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

- Freud, S. (1905/2009). Wit and its relation to the unconscious. Overland Park, KS: Digireads.com, Neeland Media, LLC.

- Goddard, C., & Gillett, H., (2006). Complications of coeliac disease: Are all patients at risk? Postgrad Med Journal, 82, 705-712. doi: 10.1136/pgmi.2006.048876

- Green, P. H. R., & Jabri, B. (2003). Coeliac disease. The Lancet 362, 383-391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14027-5

- Janis, I. L. (1982). Groupthink. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Koenig Kellas, J., & Kranstuber Horstman, H. (2015). Communicated narrative sense making: understanding family narratives, storytelling, and the construction of meaning through a communicative lens. In L. M. Turner & R. West (Eds.), Sage Handbook of Family Communication (pp. 76–90). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Langellier, K. M., & Peterson, E. E. (2018). Narrative performance theory: making stories, doing family. In D. O. Braithwaite, E. A. Suter, and K. Floyd (Eds.), Engaging Theories in Family Communication Multiple Perspectives (pp. 43-56). New York, NY: Routledge.

- McAdams, D., Reynolds, J., Lewis, M., Patten, A., & Bowman, P. (2001). When bad things turn good and good things turn bad: Sequences of redemption and contamination in life narrative and their relation to psychosocial adaptation in midlife adults and in students. PSPB, 27(3), 474-485. doi: 10.1177.0146167201274008

- McGee. M. C. (1980). The ideograph: A link between rhetoric and ideology. In C. R. Burgchardt (Ed.), Readings in Rhetorical Criticism (pp. 498-513). State College, PA: Strata Publishing, Inc.

- McKerrow, R. E. (1989). Critical rhetoric: Theory and praxis. In C. R. Burgchardt (Ed.), Readings in Rhetorical Criticism (pp. 96- 118). State College, PA: Strata Publishing, Inc.

- McLellan, D. (1986). Ideology. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mumby, D. K. (2015). Organizational communication: Critical approaches. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The concise encyclopedia of communication (pp. 429–431). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Pecchoni, L., Overton, B., & Thompson, T. (2008). Families communicating about health. In L. M. Turner & R. West (Eds.), Sage Handbook of Family Communication (pp. 306-319). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Statista (2018b). The rise of the gluten free diet: Percent of Americans on gluten-free diet with/without celiac disease. Retrieved from https://www-statista-com.du.idm.oclc.org/chart/7639/the-rise-of-the-gluten-free-diet/.

- Statista, (2016) Sales of the leading brands of antacid tablets in the United States in 2016. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/737978/us-sales-of-antacid-tablet-brands/

- Uhde, M., Ajamian, M., Caio. G., DeGiorgio, R., Indart, A., Green, P., Verna, E. Volta, U., & Alaedini, A. (2016). Intestinal cell damage and systemic immune activation in individuals reporting sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease. Gut, 65, 1930-1937. doi: 10.1136/gutjrl-2016-211964

- Van Dijk, T.A. (2006). Ideology and discourse analysis. Journal of Political Ideologies 11(2), 115–140, doi:10.1080/13569310600687908

- Wangen, S. (2009). Healthier without wheat. Seattle, WA: Innate Health Publishing.

- White, H. (1980). The value of narrativity in the representation of reality. Critical Inquiry 7(1), 5-27. No doi.

A Note on the Participants

Throughout the document, names of interview participants are noted with pseudo-names and their corresponding respondent number.

Recommended Comments

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now