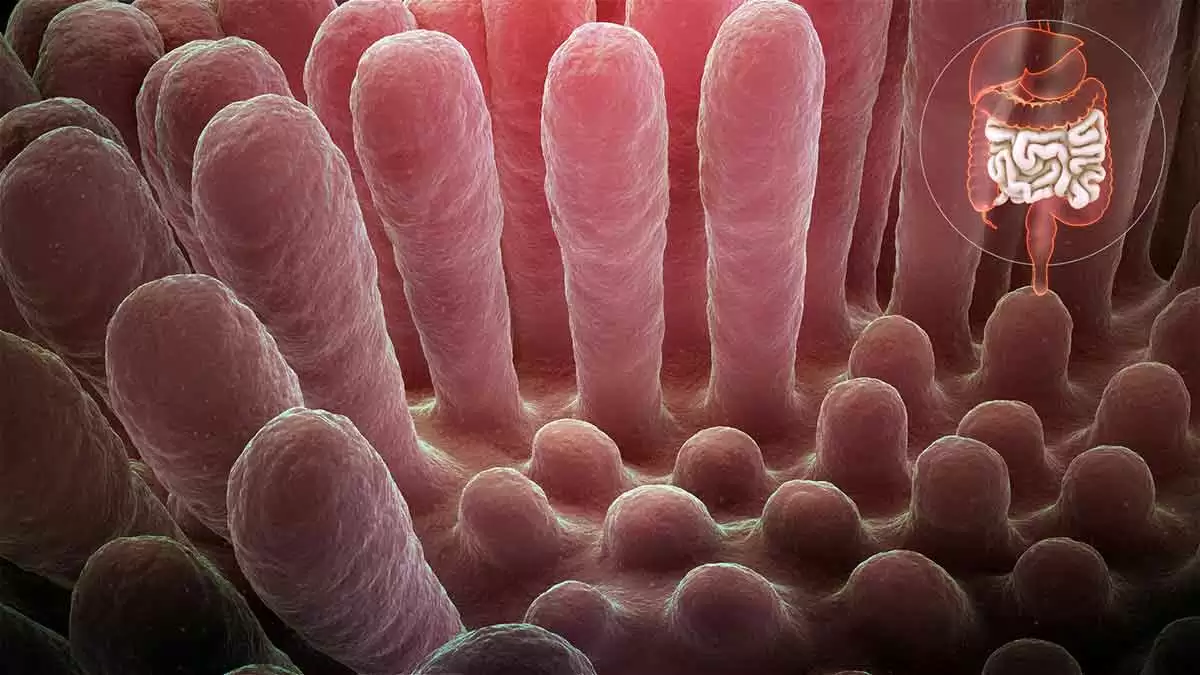

Celiac.com 02/10/2024 - Villous atrophy, a condition marked by the blunting or flattening of the microscopic structures called villi in the small intestine, is most commonly associated with celiac disease. However, emerging research and clinical observations have unveiled a spectrum of diverse conditions beyond celiac disease that can lead to villous atrophy. This article explores the lesser-known contributors to villous atrophy, shedding light on various health conditions that may present with similar histological changes in the small intestine. While celiac disease remains a prominent cause, understanding these alternative pathways to villous atrophy is crucial for accurate diagnosis, appropriate management, and a comprehensive approach to gastrointestinal health. From autoimmune disorders to infections and drug-induced reactions, exploring the multifaceted nature of villous atrophy enhances our grasp of gastrointestinal pathology and guides clinicians toward more nuanced and personalized patient care.

Other Conditions Associated with Villous Atrophy

In the following sections, we delve into a comprehensive exploration of diverse health conditions intricately linked to villous atrophy, shedding light on their unique associations and implications for gastrointestinal health.

Eosinophilic Enteritis

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

Eosinophilic enteritis is an inflammatory disorder characterized by an increased presence of eosinophils in the gastrointestinal tract. Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell involved in the immune response. In eosinophilic enteritis, these cells infiltrate the walls of the intestines, causing inflammation and damage. This inflammatory process can lead to various symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and malabsorption. In some cases, the inflammation may result in villous atrophy, affecting the absorptive capacity of the small intestine. Diagnosis often involves endoscopic procedures with tissue biopsy to evaluate the extent of inflammation and associated damage.

Crohn's Disease

Crohn's disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, from the mouth to the anus. In the small intestine, Crohn's disease can cause inflammation and damage to the intestinal lining, leading to complications such as strictures and fistulas. In some cases, individuals with Crohn's disease may experience villous atrophy, particularly in areas of the small intestine affected by inflammation. The severity of villous atrophy can vary among patients with Crohn's disease, and its presence may contribute to malabsorption issues and nutritional deficiencies. Management often involves anti-inflammatory medications, immunosuppressants, and, in severe cases, surgical intervention to address complications.

Giardiasis

Giardiasis is an intestinal infection caused by the parasite Giardia lamblia. This parasitic infection can lead to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and bloating. In addition to the acute phase of the infection, chronic giardiasis has been associated with villous atrophy in some cases. The mechanisms by which Giardia lamblia causes villous atrophy are not fully understood, but it is believed to involve both direct damage to the intestinal lining and an immune response triggered by the presence of the parasite. Diagnosis typically involves stool tests to detect the parasite, and treatment includes antiparasitic medications.

Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID)

Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID) is a primary immunodeficiency disorder characterized by impaired antibody production, leading to increased susceptibility to infections. Some individuals with CVID may experience gastrointestinal symptoms, including chronic diarrhea and malabsorption. In severe cases, villous atrophy can occur, impacting the absorption of nutrients in the small intestine. The association between CVID and villous atrophy underscores the complex interplay between the immune system and the intestinal mucosa. Management involves immunoglobulin replacement therapy to address the immune deficiency and supportive measures for gastrointestinal symptoms.

Autoimmune Enteropathy

Autoimmune enteropathy is a rare autoimmune disorder that primarily affects the small intestine. In this condition, the immune system mistakenly attacks the cells of the intestinal lining, leading to severe inflammation and damage. Villous atrophy is a characteristic feature of autoimmune enteropathy, affecting the absorptive surface area of the small intestine. Individuals with autoimmune enteropathy often present with persistent diarrhea, malabsorption, and failure to thrive. Diagnosis requires extensive evaluation, including endoscopic procedures and tissue biopsy. Treatment involves immunosuppressive medications to modulate the autoimmune response and manage symptoms.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Advanced Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection can result in various gastrointestinal complications, affecting both the upper and lower parts of the digestive tract. HIV-associated enteropathy may involve villous atrophy, contributing to malabsorption and nutritional deficiencies. The mechanisms leading to villous atrophy in HIV infection are multifactorial, involving both direct viral effects and immune-mediated processes. Additionally, opportunistic infections and other HIV-related complications can further impact the gastrointestinal mucosa. Management includes antiretroviral therapy to control HIV replication and supportive measures to address nutritional deficiencies and associated symptoms. Regular monitoring and a multidisciplinary approach are crucial in the care of individuals with HIV-associated gastrointestinal conditions.

Dermatitis Herpetiformis (DH)

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a chronic skin condition characterized by intensely itchy, blistering skin lesions. While DH primarily manifests as a skin disorder, its connection to celiac disease is well-established. Both conditions share a common trigger: gluten ingestion. DH is considered the skin manifestation of celiac disease, and individuals with DH often have underlying gluten sensitivity. The immune response triggered by gluten in susceptible individuals leads to the formation of IgA antibodies, which deposit in the skin, causing the characteristic skin lesions. While DH predominantly affects the skin, it is crucial to recognize its association with celiac disease, as individuals with DH may also experience villous atrophy in the small intestine. Therefore, a gluten-free diet is not only essential for managing skin symptoms but also for addressing the underlying celiac disease and preventing intestinal damage. Diagnosis involves skin biopsy for characteristic IgA deposits and, in some cases, intestinal biopsy to assess the extent of villous atrophy. Treatment primarily revolves around strict adherence to a gluten-free diet, often complemented by medications to control skin symptoms. Managing DH effectively requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving dermatologists, gastroenterologists, and dietitians to address both the skin manifestations and the underlying celiac disease.

Idiopathic Sprue

Idiopathic sprue is a term used for cases of sprue (malabsorption syndrome) where the cause is unknown. It may include cases that do not fit the criteria for celiac disease or other known causes of malabsorption. It shares some features with celiac disease, such as malabsorption and damage to the small intestine, but it lacks specific diagnostic markers for celiac disease. Diagnosis may involve excluding other causes of malabsorption, and it may be considered when typical celiac disease markers are absent.

Tropical Sprue

Tropical sprue is a malabsorption syndrome that occurs in tropical regions, and its exact cause is not fully understood. It is thought to be associated with infections or environmental factors. It presents with symptoms of malabsorption, such as diarrhea, weight loss, and nutritional deficiencies. It is more commonly observed in tropical regions but can occur in non-tropical areas as well.

Collagenous Sprue

Collagenous sprue is a rare disorder characterized by collagen deposition in the small intestine. The cause is not well-established. It leads to malabsorption and features similar to celiac disease but is distinguished by the characteristic collagen band in the intestinal lining. Diagnosis involves histological examination of small intestinal biopsies. The management of collagenous sprue may involve a combination of treatments, including a gluten-free diet and immunosuppressive medications. Corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants may be prescribed.

Peptic Duodenitis

Peptic duodenitis, a condition characterized by inflammation of the duodenal lining due to exposure to stomach acid, shares a commonality with celiac disease in its potential to induce villous atrophy. In peptic duodenitis, the inflammatory response triggered by gastric acid can extend into the duodenum, disrupting the delicate balance of the intestinal mucosa. This sustained inflammation may lead to changes in the architecture of the small intestine, including the villi, finger-like projections crucial for nutrient absorption. The damage incurred can result in villous atrophy, akin to the characteristic intestinal changes observed in celiac disease.

Helicobacter Pylori

Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium known for its association with gastric ulcers and gastritis, has been implicated in gastrointestinal conditions that extend beyond the stomach, including potential involvement in villous atrophy akin to celiac disease. The presence of H. pylori in the duodenum and small intestine has been linked to chronic inflammation and alterations in mucosal architecture. The bacterium's ability to induce immune responses may contribute to the damage of the intestinal villi, compromising their structure and functionality. This shared consequence of villous atrophy highlights the interconnectedness of various gastrointestinal disorders and underscores the need for comprehensive investigations to discern the specific triggers and mechanisms at play. While celiac disease and H. pylori-related duodenal changes differ in their etiology, understanding the potential overlap in their impact on intestinal health is crucial for accurate diagnosis and tailored therapeutic interventions.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is recognized for its capacity to disrupt the normal balance of microorganisms in the small intestine, leading to various gastrointestinal manifestations. In some cases, SIBO has been associated with mucosal damage, mirroring the villous atrophy observed in conditions like celiac disease. The overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine can interfere with nutrient absorption and trigger an inflammatory response, potentially contributing to the erosion of the intestinal villi. While the mechanisms differ from those in celiac disease, the shared outcome of villous atrophy underscores the intricate relationship between dysbiosis and intestinal health.

Lymphoma

Lymphoma, a form of cancer that originates in the lymphatic system, can exhibit parallels with celiac disease in terms of inducing villous atrophy. In some cases, individuals with longstanding untreated celiac disease may face an elevated risk of developing enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL), a rare but serious complication. EATL is characterized by the infiltration of malignant T lymphocytes into the intestinal mucosa, leading to structural changes reminiscent of villous atrophy. While lymphoma and celiac disease differ fundamentally, the shared manifestation of villous atrophy underscores the intricate interplay between chronic inflammation and the potential oncogenic transformations within the gastrointestinal milieu.

Thiamine (Vitamin B1) Deficiency

There is some old research that indicates that prolonged low thiamine (vitamin B1) may cause thinning of the microvillus membrane.

While these conditions may share some clinical features with celiac disease, the differences in their etiology, histopathology, and diagnostic criteria make them distinct entities. Accurate diagnosis and differentiation often require a thorough clinical evaluation, including serological tests, histopathological examination, and consideration of geographic or idiopathic factors. Consulting with a gastroenterologist or healthcare professional is essential for proper diagnosis and management.

Drug-Associated Enteropathy: Medications Associated with Villous Atrophy

Understanding the intricate interplay between medications and intestinal well-being is paramount for individuals managing chronic health conditions. While medications play a pivotal role in alleviating symptoms and improving overall health, certain drugs may harbor the potential to influence the delicate environment of the small intestine. This section delves into the impact of various medications on the intestinal villi, focusing on conditions that may lead to villous atrophy. From common pain relievers to immunosuppressive drugs, the discussion aims to shed light on the nuanced relationship between medications and gastrointestinal health. It underscores the importance of informed healthcare decisions, proactive monitoring, and open communication between patients and healthcare providers to mitigate potential complications and ensure optimal intestinal function during the course of medical treatments.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to alleviate pain and inflammation, but prolonged and excessive use has been associated with adverse effects on the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. NSAIDs can cause irritation and inflammation in the small intestine, potentially leading to villous atrophy. The mechanism involves the inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzymes, which play a role in maintaining the integrity of the GI mucosa. Individuals relying on NSAIDs for chronic pain management should be cautious and work closely with healthcare providers to monitor and mitigate potential GI complications.

Immunosuppressive Drugs

Immunosuppressive drugs, such as methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil, are crucial in managing autoimmune conditions and preventing organ rejection after transplantation. While these medications target the immune system to curb excessive responses, they may also impact the gastrointestinal lining. Long-term use could lead to intestinal complications, including villous atrophy. Healthcare providers prescribing immunosuppressive drugs carefully assess the risk-benefit profile for each patient and monitor closely for potential adverse effects on the GI tract.

Chemotherapy Drugs

Chemotherapy, a cornerstone in cancer treatment, aims to eradicate rapidly dividing cells, including cancerous ones. However, the impact isn't limited to tumors, and normal, healthy cells may also be affected. The rapidly renewing cells in the small intestine are particularly susceptible, potentially resulting in damage to the villi and compromising the absorptive capacity of the intestines. Individuals undergoing chemotherapy should discuss potential gastrointestinal side effects with their oncologist to address and manage any complications that may arise.

Some Antibiotics

Certain antibiotics, such as tetracycline and ampicillin, may disrupt the balance of the gut microbiota, leading to gastrointestinal disturbances. While these antibiotics target harmful bacteria, they can also affect beneficial microbes, influencing the overall health of the intestinal lining. The intricate relationship between antibiotics and the gut underscores the importance of judicious antibiotic use and, when necessary, the simultaneous administration of probiotics to support a healthy gut environment.

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs), commonly prescribed for acid reflux and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), reduce stomach acid production. Prolonged use of PPIs has been linked to changes in the small intestine, potentially impacting the structure and function of the villi. Individuals relying on PPIs for an extended period should collaborate with healthcare providers to assess the necessity of continued use and explore alternative approaches to manage acid-related conditions.

Opioid Pain Medications

Opioid pain medications, including morphine and oxycodone, are known for their analgesic properties but are also associated with side effects such as constipation. Chronic use of opioids may lead to intestinal issues, affecting the normal functioning of the small intestine. It is crucial for healthcare providers to carefully manage opioid prescriptions, considering the potential impact on the gastrointestinal tract, and to explore alternative pain management strategies whenever possible. Patients should communicate openly with their healthcare team about any digestive issues experienced during opioid therapy to ensure timely intervention and support.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the journey through conditions associated with villous atrophy extends far beyond the realms of celiac disease. This exploration has highlighted the intricate interplay of various factors that can impact the health of the small intestine, leading to structural changes in the form of villous atrophy. Recognizing these diverse contributors is pivotal for healthcare professionals navigating the complexities of gastrointestinal disorders. As we deepen our understanding of the nuanced manifestations of villous atrophy, we pave the way for improved diagnostic accuracy and tailored treatment strategies. The heterogeneity of conditions linked to villous atrophy underscores the need for a holistic and individualized approach to patient care, ensuring that the intricacies of each case are addressed with precision and empathy. Through continued research and clinical vigilance, we strive to unravel the mysteries of these conditions and enhance the well-being of individuals facing the challenges of villous atrophy.

Further reading on the topic of other causes of villous atrophy:

Recommended Comments

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now