Celiac.com 06/25/2021 - Chapters of Gluten-Centric Culture – The Commensality Conundrum are being published quarterly in the Journal of Gluten Sensitivity. Dr. Duane will be holding small discussion workshops starting July, 2021 for those interested in diving into the material in the book (please see below for details). Ideologies as explained in chapter one can be summarized as taken for granted truths. These "truths" govern how we interact with each other. Dr. Duane conducted a nation-wide study of over 600 people who live with food sensitivities while earning her PhD. This work is the result of that study. Throughout the document, study participants are quoted. Names have been changed to protect the identity of study participants.

Ideologies evolve and change depending on cultural norms, or who and what are influential at a given time. They are defined by influencers like the media, what celebrities or politicians say, what our momma taught us about etiquette, what the government says is a healthy diet, and what we learn in church. Nobody questions these until they are found to be untrue, such as when we are diagnosed with a disease that makes us unable to consume virtually any processed food. Then we come into conflict with these "given truths." Ideologies cause us trouble when "bumped" up against, because we have no language to describe them. We're vaguely aware we've done something to upset the apple cart based on the reactions of others, but we can't really put our finger on what it is or what to do about it. When we don't go along with what is commonly thought to be true, we feel awkward in social settings, but it isn't something easily discussed. Giving "language" to this empowers us to call out some of these "truths" and have meaningful conversations with those we love. This way, we can rethink our definitions, and teach those around us to see it our way. Let's start by examining the first ideology I am terming reluctant tolerance and how it was formed by various influencers.

Figure 2.1 – Gluten Sensitive (Licensed with permission from Comics Kingdom (Bizarro).)

Reluctant Tolerance

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

(Note: Excerpts from this chapter were previously published in the Journal of Gluten Sensitivity in an article entitled The Media Encourages Negative Social Behavior Towards Gluten-Free Dieters, January, 2018.)

The media is very influential on swaying opinions and providing role models for behavior. What entertains us often becomes how we act in social settings. "Gluten" is often the punch line for celebrities. For example, a popular talk show host expressed an ideology of reluctant tolerance when referring to people following the gluten free diet saying, "Some people can't eat gluten for medical reasons… that I get. It annoys me, but that I get" (ABC, 2018). This cheap laugh illustrates the reluctant tolerance ideology. Reluctant tolerance pervades our society, with people begrudging those who have restrictive dietary needs. Comments like this perpetuate the feeling. George (#67, celiac.com) reacts to the comment as follows:

I found the video very telling. It exemplifies what happens to society's point of view when something becomes ‘trendy' whether there is a genuine problem some people face or not. It can be bad enough when popularity of a diet/fad/idea/opinion causes harm to businesses and industry, but it's even worse when it gets down to an individual's health and what amounts to casual poisoning. … What a shame we have to deal with that sort of jaded disbelief.

I remember a long time ago when late-night comedians relied on offensive ethnic jokes. Today, that kind of joke is off limits. What happened to change that? You don't hear other slurs any more on TV, likely because that reluctant tolerance attitude ultimately wasn't tolerated by those maligned by the jokes. Hallelujah! Similarly, I think we need demand respect and say, "Hey, we have a serious disease. Stop joking about it. You erode the gravity of it when you do."

What contributes to this reluctantly tolerant attitude toward gluten? Let's examine some examples in the media that may play a part in forming the public's opinion about it. Negative comments about the gluten-free diet are replicated in situation comedies, in memes, comics, YouTube videos, and other forms of media. Those with allergies or gluten intolerance are regularly targeted for ridicule. And, gluten sensitivities are frequently treated with skepticism. For example, a celebrity chef said he had "a gluten-free intolerance." He notes, "I can eat bread just fine, it's the people who insist on proselytizing about their medically dubious grain-free lifestyles that piss me off" (Filloon, 2018). This type of comment from celebrities may influence how seriously a restaurant server takes individuals who disclose they have celiac disease. The server, taking his cue from the celebrity chef, may jadedly regard an order for a gluten free meal as an inconvenience by assuming the person requesting is evangelizing. He may only comply with the request with reluctant tolerance, whereas if he hadn't heard that popular chef's comment, he might have had a more willing attitude to the special-needs patron.

Consider an episode of a popular comedy series, when a young guest of the family asks for a gluten-free breakfast. The mother in the family greets his request with exasperation. The show ends with the guest abandoned on a deserted island, forgotten by the entire family. Another comedy, the family mocked a sibling's girlfriend character with multiple allergies by taking shots of whiskey every time the girlfriend mentioned another item she's allergic to, without the girlfriend knowing why they were doing that. They "othered" her, and snickered at her special needs behind her back. This scene reinforces the attitude that those with disabilities as weak and worthy of ridicule. It makes light of the real threats of living with allergies. As I watched these two episodes, chuckling along with the rest, I thought to myself, "Do these jabs on TV influence my friends and family to question my serious reaction when I consume gluten?"

An episode of a popular children's series is probably the most disturbing example of shunning the person with food sensitivities. In the scene, children throw gluten-containing pancakes at a boy, after his nanny informs them the boy cannot eat them. Would the children watching later imitate this behavior? Researchers Huesmann and Taylor, 2006 think so. They point out that behavior viewed on TV can present a "threat to public health" and lead to "an increase in real-world violence and aggression" (p. 393). Even if it does not incite violence toward food sensitive individuals, these depictions diminish their credibility. Scenes like those described above undermine the need for safe food, pressuring those with celiac disease or food sensitivities to conform and be "normal," perpetuating ideologies of reluctant tolerance, and favoring able-bodied people.

A popular adult series (Parker, 2014) put a new twist on the reluctant tolerance of gluten ideology in a recent episode. In this case, however, it favors those who are following the diet. In it, town council members dread encountering a teacher, because he only talks about how well he feels on the gluten free diet. In this episode, a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) representative speaks on the recommended diet for Americans, stating that gluten won't cause catastrophic illness and is safe to eat. From the audience, the teacher yells, "if it is safe, then eat it." With some reservation, the USDA representative drinks the distilled gluten from his presentation table. Seconds pass, and the USDA representative seizes in pain. A moment later, a key body part detaches from his body and flies around the filled auditorium. Mayhem results. The citizens hurriedly rush home to throw away all of the foods in their kitchens containing gluten. Even though I started watching this episode with some skepticism, expecting to see reluctant tolerance for gluten, I was falling off of my chair laughing. It was very funny, favoring those avoiding gluten. The episode concludes with the USDA turning the food pyramid upside down, making grains the food to eat the least of, and meats the food to consume predominantly. Though irreverently hysterical, this is an example of the ideology that gluten is the target for derision, as something to be reluctantly tolerated.

We Imitate What We See

Gluten "performances" on TV and in the movies serve as role models for members of society, instructing us on how to act in social interactions. There is an abundance of research that finds we imitate what we see in the movies or on TV in real life. For example, those who hear violent lyrics tend to display more hostility and aggressive thoughts than participants who were exposed to neutral songs (Anderson, Carnagey, & Eubanks, 2003). Exposure to media violence is highly correlated with bullying behavior (Lee & Kim, 2004). Humans mimic what they are exposed to. If we see someone smoking in a movie or on TV, we are likely to be influenced to smoke (Villanti, Boulay, & Juon, 2010). If we see a character we identify with eating, we are likely to eat too (Zhou, 2016), and if we see someone having sex, we are influenced to imitate that behavior as well (Collins, Martino, & Elliot, 2011). Similarly, if we see violent behavior on TV, we are likely to be more violent (Huesmann & Miller, 1994). In the same way, exposure to negative media, or powerful perspectives on the gluten free lifestyle, are likely to influence ideological "truths." TV and celebrities influence how people interact in all aspects of daily life (Hall, 2012), even their political views and affiliations (Nownes, 2012). Celebrities join the blitz by mocking those who do not consume gluten.

Celebrity Quips

A popular etiquette writer says, "As far as I can tell, the biggest side effect of a gluten sensitivity is that you actually become the number one symptom: a huge pain in the ass." Celebrities that dish gluten vituperations form ideologies that are "the touchstone of both truth and falsehood" (Gellner, 1991, p. 123–124). Though this writer's crass comment maligns those with gluten sensitivities, most people with celiac disease will admit, their restrictions are indeed a pain in the ass. Ideologies are further perpetuated by celebrities' quips in the popular press. A celebrity chef said, "Your body is not a temple, it's an amusement park. Enjoy the ride," and another chef said, "The only time to eat diet food is while you're waiting for the steak to cook." These quotes endorse dietary indulgence, positioning the restrictive diet as a form of repression. Likewise, a celebrity's casual endorsement of virtually anything can influence America's consumption of it (Kinsella, 1997). For example, an influential talk show host recently declared publicly, "I love bread." I love this talk show host and greatly respect her opinion. But, does her comment cause others like me to question our decision to avoid bread? I admit she is speaking for herself but because she is so influential, her comment makes me feel abnormal for not eating bread. And even though I know what it will do to me, I want to be accepted by the others who follow this host. Celebrities have great influence on people's thoughts and actions. Self-harming behavior could translate into a person with celiac disease taking a risk of consuming the slightest amount of gluten due to peer pressure by celebrities (Hilton, 2016). Collectively, these media examples cue audiences that anyone who asks for dietary accommodations is annoying and should only be reluctantly tolerated. Comments like these perpetuate the gluten-doubt ideology.

Gluten-Doubt

An actress called the gluten free diet "the new cool eating disorder," a great example of the gluten-doubt ideology (heath.com). Though ideologies stemming from religion, government publications, media, and pop culture often guide behavior, we are not always aware they are driving our actions. These associations are deduced anecdotally. Ideologies are the impetus for how people explain their behaviors and decisions, which creates a consciousness that impacts social practices (Rohan, 2000). The pro-gluten website pharmafist.com posts a comic stating, "Let's put an end to the gluten free trend" (Bernard, 2016) perpetuating the ideology that celiac disease is not a real or serious illness, but rather a trend. It creates an environment of suspicion for those requesting gluten free foods and instills doubt among others. A hostess might see this comic as she prepares food for her extended family, which includes a request for a gluten free option. While the hostess may already feel inconvenienced by the request to alter her menu, the "gluten trend" comic may increase her resentment over having to make special dispensations, or may cause her to question the relative's true need for a gluten free diet. A restaurant held a celebration of gluten calling the eight-course dinner "(It's) A Celebration of Gluten (Bitches)" as a way to refute gluten-free meal requests. Whether conscious of it or not, the restaurant ad casts an ideology of gluten-doubt on the validity of those requesting gluten-free foods.

Politicians on the Bandwagon

Even politicians jump on the "mock-gluten" crusade. A presidential candidate weighed in on the gluten free bandwagon, saying he will have, "the gluten-freest presidency in history" and posted a slogan "Dam tootin, no gluten," though it was clear this person did not advocate a gluten free diet. This inauthenticity makes the post appear as a feeble attempt to attract voters who pay attention to their diets. Another politician stated that if elected, he would not provide gluten-free meals to the military, in order to direct spending toward combat fortification, discounting those with celiac disease and implying that gluten free meals are a waste of money. This is also an example of the able-body bias ideology discussed below.

On a T-Shirt, for Cryin' Out Loud!

America's fascination with gluten-free jabs extends from television shows, news headlines to (if you can believe it) T-shirts and greeting cards. Etsy.com sells T-shirts with slogans that say: "Extra gluten," and "This shirt is gluten-free." Doormats are available too that say, "No gluten or BS allowed beyond this point." There is a greeting card that says, "Every moment is a gift until someone puts flour in the gravy." It seems no matter where you look, whether on TV, or walking down the street glancing at someone's T-shirt, there are media vilifying gluten, perpetuating the reluctant tolerance ideology. Consider the New York Times headline, "The Myth of Big, Bad Gluten" (Myth, 2015), which aligns gluten with the fairytale "big, bad wolf." Business Insider published a YouTube video on, "Why Gluten Sensitivity (a 15 billion dollar industry) is fake," which casts doubt on non-celiac gluten sensitivities (NCGS). Further, Business Insider calls Tom Brady's gluten-free, dairy-free diet "insane" (Brady, 2017). The reluctant tolerance of gluten ideology bombards us in virtually every arena.

Able-body Bias

The able-body bias ideology refers to a predisposition to prefer those who are "fit and able" to those with disabilities. Popular culture and media further purvey able-body bias ideologies concerning food and behavior with its trivialization of allergens in food. For instance, in a popular family-oriented movie, a prominent food provider is warned by the parents of a child with peanut allergies to ensure that the corndog he's handed the child is peanut free. Just as the child bites into the corndog, the food provider remembers it was fried in peanut oil. This is meant to be a humorous moment in the film, implying that the parents' protective warnings are smothering the child. But parents raising children with peanut allergies attest that it is quite far from funny (Duane, 2018). Not providing "access" causes others to view the disabled as an inconvenient exception (Titchkosky, 2009). Able-body bias ideologies perpetuate the notion that only weaklings have food sensitivities.

Another able-body bias scenario that haunts those with celiac disease is the event of a national disaster where the Red Cross provides foods. Rose (#5) describes her concern: "They talk about when there are disasters and the Red Cross will come in and bring food to people. What do they bring them? They bring them [gluten containing] sandwiches. I wouldn't be able to eat that." Further, elderly people with celiac disease wishing to live in a retirement home may be turned away because the kitchen cannot comply with their restrictions. I discuss the American Disabilities Act (ADA) in detail in Chapter 10, but it does not apply to food services in eldercare facilities. Though many offer gluten-free menu options, currently, there are only eight certified-gluten-free elderly homes out of 245,000 retirement communities in the United States (They are: Grandview Terrace with three GLUTEN FREE-certified locations and GenCare Lifestyle with five communities in AZ and WA). The able-body bias ideology mandates that everybody can eat gluten, and casts doubt on those who cannot. This puts people who need care from the Red Cross, and senior care in a real predicament. Closer to home, able-body bias affects those in a family who feel they are the "only one" in the family with celiac disease.

Many people who live with the disease state that other family members have a "for them, not us" mentality, ignoring genetic markers or symptoms that indicate they may have it too (Jones, 2013, p. 70). For example, Isla (#39) said that after she was diagnosed, she wrote to her relatives in her family Christmas card that she has celiac disease, that it is genetic, and that they should consider being tested. Nobody responded, though she feels sure that others have it after observing their symptoms. She said she felt alienated by their non-responsiveness. Their silence implied, "It's your disease, not mine." (This ideology will be discussed at length in Chapter 5.) Whether accidentally cross-contaminated, intentionally sabotaged, or incessantly urged to consume gluten-containing foods, those with celiac disease live in a day-to-day state of vulnerability. Robert (#12) reflects on a family gathering where he asked his aunt about the cheesecake ingredients. She swore it was her recipe and that there was no gluten in it. The next day, he was sick. He called his aunt who then admitted she purchased the cheesecake and had not checked the ingredients. She either did not fully understand his condition or did not take it seriously, showing how ideologies interplay. Her behavior embodied the gluten-doubt, able-body bias, and the I-Know-Best, ideologies (discussed below).

Sorta Scientific Ideologies

Realizing that "ninety-nine percent of people who have a problem with eating gluten don't even know it" (Hyman, 2013), in time, Americans may understand the importance of taking gluten free requests seriously, though scientific headlines confuse the public. Misleading "scientific" headlines giving only limited sound bites play a part in perpetuating negative gluten ideologies. Society relies on scientists, the medical community, and the press to synthesize and share new health discoveries and findings, so they may benefit the population at large. "The sheer quantity of science-based controversies in modern society makes them an interesting phenomena" (Brante, 1993, p. 188). Since the 1950's, contradictory scientific data has been a feature in the news, particularly about food and its affect on the human body, and more recently, we are regularly bombarded by it. Scientific discoveries are largely understood to be credible and reliable sources of information, which then crystalize into ideologies and guide meaning. One day a food is maligned, and the next it is upheld as "health food." For example, contemplate how an authoritative voice reporting the news headline, "Gluten-free diet not healthy for everyone" (CNN, 2018) may affect a person who then adjusts her diet based on this "distorted knowledge" (Therborn, 1980, p. 8). Conversely, the headline, "Is gluten bad for you?" seems to contradict the previous headline (Healthline, 2020). Contradictions such as this happen regularly, confusing most audiences.

Another headline asserts, "Health issues … are sometimes mistaken for gluten sensitivity" (U.S. News, 2018); therein, the article describes ailments that imitate symptoms of gluten sensitivity, perpetuating the gluten-doubt ideology on those who eliminate gluten from their diet. Scientific ideologies presented in the media often omit valuable information and introduce inaccuracies into public consciousness (Fahnestock, 1998). Scientific fact is a powerful source of firmly held ideologies. Often the public follows surface-level scientific evidence without questioning it. These "facts" may have unintended consequences in relation to food and food sensitivities. For example, the nightly news lead may assert, "More people go gluten free than need to, study finds" (NBC News, 2016), which may cause suspicion among those living with someone following a gluten free diet. Such news reports rarely explore the research in detail, but the headline sound-byte has nonetheless influenced thinking, perpetuating gluten-doubt on the decision to live a gluten free lifestyle. Grace (#17) describes how her husband repeatedly challenged her to eat gluten, asking, "How much can you have? Can't you just have a crumb?" Her husband did Internet research searching for "scientific evidence," to prove her wrong when she resisted. We've examined examples from the popular press and media, but those with gluten sensitivities face another dominant ideology – the I-Know-Best ideology.

I-Know-Best Ideologies

The I-Know-Best ideology centers on someone feeling superior to the person or people they commune with. This transfers to attitudes about food. For example, Kaya (#54) has a friend that works in a restaurant that she frequents. The friend told Kaya that the chef and the workers in the kitchen say, "What they don't know, won't hurt them" implying that if there is a little gluten in the food, it is OK. Knowing how Kaya reacts to gluten, the friend spoke to the restaurant manager who discounted her concerns by saying, "Don't rock the boat." This reflects an I-Know-Best ideology where the head chef, workers, and restaurant manager have superior intelligence to anyone asking for a gluten free meal. Attitudes like these make dining out a game of Russian roulette for the person with celiac disease. Kaya decided to avoid restaurants all together, and says, "I do not miss the nervousness I had about eating out." Patrons with celiac disease need to trust that their requests for a "clean," gluten-free meal is taken seriously by the server, chef, and even the restaurant manager.

While most people look forward to eating out, pairing flavors with wine, and the excitement of what a chef prepares that day, those with celiac disease must assess every ingredient before consuming a single bite. Many restaurants do not offer gluten free dishes, or if they do, they often disclaim that foods served may be cross-contaminated, forcing the celiac disease patron to decide whether or not to eat. This I-Know-Best attitude is illustrated in a report of a chef saying, "People who claim to be gluten intolerant don't realize that it's all … in their heads. … I serve ‘em our pasta, which I make from scratch with high gluten flour" (Moore, 2013, p. 36). Similarly, Emery (#45) describes a NYC restaurant manager's reaction to her request for gluten-free food, saying he "went off about food allergies, and how it's a conspiracy, and how nobody really has it." This illustrates how the burden of proof rests on the celiac disease sufferer, who may react to as little as "100 mg of gluten" (Green & Jabri, 2003, p. 386). Both of these examples illustrate I-Know-Best ideologies where the chef and manager imply they know more than anyone else about gluten intolerance, discounting the need for a strict gluten-free diet, and objecting to patrons asking for it. This attitude depicts the "punishment" that one endures when defying existing ideologies, and ultimately discourages those with celiac disease (and their companions) to avoid going out to eat. Cara (#53) reports, "I just can't do this. Getting this sick is not worth eating out." Madeline (#57) echoes, "I can't believe how little it takes to cause a reaction."

The I-Know-Best ideology is further illustrated by Eleanor's (#20) report that a waiter said, "Oh, you're one of those people," when she asked for a gluten-free meal. Skylar (#64) describes a waiter at a fast food sandwich shop who asked her if her gluten free request was a "preference or an allergy," presumably to discern the severity of her dietary needs. Claire (#25) conveys her embarrassment as her table companions listened carefully to her order, as she broke the fit in at all costs ideology by asking for special treatment (discussed below). Now, to deal with it she said, "I usually go in or call beforehand, rather than having everyone sit and listen to my conversation." Most feel vulnerable when hungry, and nothing to eat can cause more extreme responses as shown by Sadie (#41): "When I ordered at a restaurant specifying my needs, and the waiter got to someone else, my dining companion said, ‘I want EXTRA gluten'" thus undermining Sadie's request. Mockery such as this is perpetuated in the following comic:

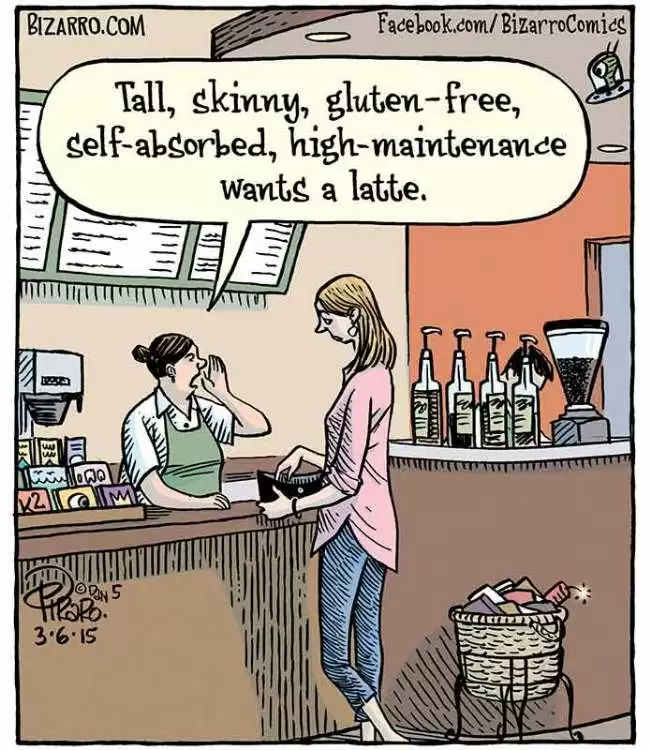

Figure 2.2 – High-Maintenance Wants Latte (Licensed with permission from Comics Kingdom (Bizarro).)

Figure 2.2 depicts a woman ordering a latte to suit her dietary needs. The barista insults the customer's character, implying "she is self-absorbed and high-maintenance" discounting her request. The barista dismisses the woman and mocks her as one who pretentiously dares to step out of line. The comic suggests that the patron's response to gluten is self-indulging, not physical. It provides another illustration on how multiple ideologies interplay. Here we see the reluctant tolerance, gluten-doubt, able-body bias, and the I-Know-Best ideologies, as well as a sexist ideology that states that women are overly emotional blended with the belief that "gluten" is an acceptable subject for mockery. This comic perpetuates the ideology that the "server knows best" or is the "ultimate judge" of whether or not the patron needs gluten free food, discounting her intelligence, and putting her health at the mercy of the server.

The Lord Knows What Is in My Heart

Christians refer to bread as the "staff of life." Bread is a sacred food (de Certeau, et al., 1998), and those who cannot consume it to sanctify the scriptures in the Bible feel less pious at best, and excluded from the communal practices of the church at worst. For example, in the Catholic Church, the Pope issued an edict that all hosts must contain gluten (Vatican, 2017). The practice of communion in the Catholic Church emphasizes how the Pope's perception about gluten permeates other levels of social interaction. Specifically, he said:

Low gluten hosts (partially gluten-free) are valid matter, provided they contain a sufficient amount of gluten [emphasis added] to obtain the confection of bread without the addition of foreign materials and without the use of procedures that would alter the nature of bread" (Vatican, 2017).

The prescribed amount of gluten exceeds the 20 parts per million U.S. standard defining gluten free, and means that Catholic individuals with celiac disease must consume gluten, if they wish to partake of the Holy Sacrament. Reading further in the letter, those with celiac disease are not considered or exempted in this edict. This exclusion has an "othering" effect on the roughly twelve million Roman Catholics who have celiac disease worldwide (BBC.com). Defying the Pope by not consuming the gluten-containing host may cause worshipers to feel sinful. Cora (#36) reports:

Rather than taking communion, I just receive the wine at the church because the host has gluten in it. Now the Catholic Church is not going to offer a gluten free host, it is very isolating. The Lord knows what is in my heart, so I just take the wine in my small parish church.

Instead of treating communion as a fundamental practice, after being diagnosed and suffering the consequences of taking communion, Cora reluctantly changed her view to see it as a metaphor, and adapted her personal practice to accommodate her dietary needs. The Pope's edict has other implications as well. Others hearing that the Pope endorses eating gluten may not take the person avoiding gluten as seriously. The church is the source of widely-held beliefs (Althusser, 1971) and the implication that a little gluten won't hurt you becomes a dominant truth that transfers from church to other social interactions. Many view the Pope as a person with exceptional powers as the human closest to God. The Pope's host edict ignoring those with celiac disease illustrates the I-Know-Best ideology and the able-body bias ideologies.

USDA as a Cultural Influencer

The USDA was created to regulate and manage the farming industry in 1862. Eventually, it evolved to provide dietary recommendations to Americans. This happened at a time when men (mostly) were keeling over from heart attacks at a staggering rate. After Eisenhower suffered a very public heart attack in the 1960s, White, the President of the International Society of Cardiology, declared the American public was in the throes of a "great epidemic" called Atherosclerosis (Levenstein, 2012). The public demanded dietary direction and the USDA provided recommendations.

In 1968, Senator George McGovern contracted reporter Nick Mottern to write Dietary Goals for the United States, using Harvard School of Public Health nutritionist Mark Hegsted as his primary resource (Taubes, 2001). Hegsted was highly influenced by the research and dietary recommendations of Ancel Keys and modeled Dietary Goals after them. Keys' work advocated that Americans consume only 30% of their diet from fat calories and of that, 10% from saturated fat (Taubes, 2001). These dietary recommendations relied on evidence provided by Keys' controversial Seven Country Study, launched in 1958. Succumbing to public pressure and ignoring other research that yielded different conclusions (Lustig, 2009; Yudkin, 1972), the Food Pyramid became the pervasive model for health and endorsements by the American Heart Association (AHA), American Medical Association (AMA), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes, the National Cancer Institute, the Center for Disease Control (CDC), and the American Dietetic Associations (ADA) solidifying the diet discretion ideology in American consciousness (Levenstein, 2012). Further, as the USDA dietary recommendations were adopted, ideological slogans promoting this way of eating included:

- Watch your cholesterol intake

- Limit saturated fats

- Ask your doctor for lipid tests

- Eat to live rather than living to eat

These slogans became easy reminders to reinforce the recommendations (Charland, 1987, p. 148). Today, the 144-page USDA 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines delineate what Americans should eat. It provides five suggestions for sustaining health, advocating shifts to eating healthy, and consuming nutrient-dense foods such as fruits, vegetables, protein, dairy, grains, and oils. It states that 177 out of a total of 328 million (U.S. Census, 2019) Americans have diseases that could be prevented by dietary adjustments and physical activity (USDA Guidelines, 2015, p. vii). However, the Guidelines do not mention celiac disease or food allergies. This omission implies that everyone should eat grains and dairy, two highly allergenic foods, another example of the I-Know-Best, able-body bias, and the reluctant tolerance ideologies. It is I-Know-Best because the recommendations come from a governmental entity perpetuating the notion that those in power "know what's best for you;" able-body bias, because it does not allow for the "disabled" who cannot tolerate these foods; and reluctant tolerance because it subjugates those requesting something different from what is written in the recommendations. Yet dairy and gluten avoidance are relatively common. Data from my study indicates that 22% of respondents avoid both dairy and gluten.

The Guidelines assert: "Everyone has a role in supporting healthy eating patterns" (2015, p. 63), but the omission of allergies from such a central document discounts the prevalence of food allergies among 60 million Americans (Hyman, 2013). This omission could be one reason that the idea of the gluten-free diet triggers resistance, such as from the book entitled The Gluten Lie, saying gluten intolerance is probably not real (Levinovitz, 2015). This sentiment starts with the USDA Guidelines (by omission) and is magnified through many forms of media, food service providers, and the medical community.

Medical Myths

Many doctors continue to operate under the myth that celiac disease occurs mostly in white children and rule it out before testing adult patients (Fasano & Catassi, 2012). Some seem to think that people with celiac disease are thin and gaunt, and this is also not universally true. Naomi experienced this reaction from a gastroenterologist who told her "I don't think you have celiac disease. You are tall and you look healthy. Most people with celiac disease are short and thin." Naomi was later diagnosed with celiac disease. Some doctors erroneously believe the myth that children "grow out" of food intolerances as reported by Samantha (#29) who was diagnosed with celiac disease when she was very young. She visited a doctor as an adult who ask her, "Don't you think you've outgrown this by now?" Obviously, she didn't grow out of celiac disease. Similarly, Rose describes a lifetime of illness starting when she was young and was also told she would "outgrow" it. She had stomachaches as a child, thyroid issues, and a miscarriage in her 20s. Finally, in middle age, she flew to a specialized clinic in New York, where she was diagnosed with celiac disease. There, they told her that people do not grow out of it, and that celiac disease was likely the cause of her miscarriage and thyroid problems. She lived with it until middle-aged without even knowing she had it, and likely would not have been diagnosed if she had not been a woman of means, education, and determination.

Though celiac disease "is humankind's most prevalent genetically linked disease… [occurring] more frequently than Type 1 diabetes, cystic fibrosis, or Crohn's disease" (Fasano & Flaherty, 2014, Loc. 556), doctors are often untrained in testing for it and are influenced by many of the same dominant ideologies described above. Doctors may rely on sound bites such as everything in moderation, when discussing diet choices in brief appointments lasting an average of seven-minutes (Shanahan, 2017). This over-simplified snippet of advice does not serve those with food sensitivities or celiac disease, yet it is common practice due to insufficient nutrition education in U.S. medical schools and the I-Know-Best attitude (Adams, Kohlmeier, Powell, & Zeisel, 2010; Vetter, Herring, Sood, Shah, & Kalet, 2008). Hailey (#38) describes how her doctor prescribed one pill a day for five days, knowing the pill contained a gluten-binder. Her doctor said it's OK for that short of time. Of course, it isn't OK ever. Physicians' lack of training and reliance on taken-for-granted ideologies exacerbates the desperation felt by those who remain ill and un- or misdiagnosed, and perpetuates the gluten-doubt, and the I-Know-Best ideologies. If a doctor tells us that we can eat everything in moderation, or that we will outgrow allergies, or that a pill with gluten is OK to take, we are hard-pressed to defy that authority and ignore the advice given by our highly paid medical advisors.

Don't Mess With Bread

In Western cultures, eating represents a fundamental connection between a person and his or her environment (de Certeau, Giard, & Mayol, 1998). From garden to table, "food is forever bound to representation or culture" (Foust, 2011, p. 354). A brief review of Western celebrations and holidays confirms the centrality of gluten. In most American weddings, the bride and groom feed each other a piece of wedding cake to symbolize their unity. The cake is then distributed to guests who join the celebration (The Spruce, 2018). When that cake is chocolate, it may even elicit a sexual response because chocolate cake is associated with intimacy (LeBesco & Naccarto, 2008).

Similarly, bread's symbolism far exceeds its function as a food source. It is often treated as a sacred food (de Certeau, et al., 1998), and purging it from one's diet can present a host of religious, spiritual, and cultural complications. For instance, weddings in Poland traditionally include a loaf of salted bread and wine for the couple to eat and drink, symbolizing a life of abundance (Wedding, 2018). At wedding receptions in Russia, the bride and groom take a bite of bread held by a third party. Whoever takes the biggest bite is deemed the head of the household (Wedding, 2018). In France, the bride and groom dance under a brioche and then eat it (French Today, 2018). In American Appalachia, guests bring stack-cakes (pancakes) and pile them on a plate, adding apple butter between each layer. The couple's popularity is determined by the height of the stack (History, 2018). In America, when the bride and groom feed each other a bite of the wedding cake at their wedding reception, it symbolizes taking care of each other in their new life.

In addition to being an integral part of weddings in some cultures, bread is also a mainstay in the family dinner. Bread is such an important aspect of the Western meal that "…one does not joke around with bread." It's "the necessary foundation for all food…" (de Certeau, et al., 1998, p. 87). Ideologies impact rituals and practices such as ceremonies or traditional menus, which provide comfort and stability (Boyer & Lienard, 2006). Further, sharing indigenous food with other community members can perpetuate valued customs and rituals. "To live on one bread and one wine that is, to share food, is …a way of signifying that one belongs to the same family" (Montanari, 2006, p. 11). Bread has been an integral part of the meal for all classes of society (Montanari, 2006).

Extreme dietary changes disrupt traditional practices and challenge firmly held "truths." For example, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on white bread have come to symbolize Americana and those who shun "white bread," are considered elitist or health-obsessed. Kaylee (#52) reports, "Some people don't believe I'm happy not eating bread, and make me feel like I should [eat it]." Her comment echoes how in our western culture bread symbolizes normalcy. In fact it is so ingrained in our culture that it is a metaphor for many things such as: Breaking bread with another, which signifies human bonding rituals. The greatest thing since sliced bread refers to an innovative invention. Knowing which side your bread is buttered on implies knowing who is paying your way, bread is a synonym for money, and man doesn't live by bread alone means there is more to life than foraging a living.

Because I Said So

Agency refers to how much power a person has in a given situation. For example, traditional high agency is awarded to people in a dominant position, such as the head of the household, the income producer in the home, or the homeowner. These elements yield implied power. Those in a subordinate position have less agency, or rights to speak out for themselves to demand that their needs are accommodated. Those without agency often "go along to get along" and suffer the consequences. They try not to make waves or cause rifts. In the interviews, I asked the question, "How has being gluten-free affected your position in the household?" Many told stories of how the family stepped up to help the person who needed to follow a special diet such as Victoria (#15) who said, "My family always puts my needs first." Or Peter (#34), who says, "My family works hard to keep me from getting sick." Madelyn (#37) said, "my son labeled a portion of the pantry: ‘Mommy's special foods.'" These examples show functional family environments where members have agency, and where their needs are taken seriously. Contrastingly, some conveyed an absence of agency as they described living in households where others consumed gluten, causing them to be cross-contaminated and repeatedly sick. For example, Alex (#1) describes the following scenario:

I remember when I first started cooking gluten-free in a shared household with my parents. I had this habit of taking out freezer paper and laying it on the counter to have a nice safe working environment. I cooked on it with my own dedicated pan, spoon, and pot. One day I went in the kitchen to make breakfast. I started fixing my stuff and there was a crumb on the counter and I thought it was almond meal. It looked like almond meal, something I've been making. I picked it up and put it in my mouth. I wondered where the heck my spoon was and it looked over in the sink and there was my dedicated spoon covered in sticky, white, gooey stuff. And all of a sudden it dawns on me and I get the sinking feeling. My mom had used my pot and my spoon and had made cream of wheat. What I had put in my mouth was cream of wheat! She used my utensils and contaminated them. I thought, "Oh my God!" Yeah, that day didn't end well.

Alex describes a situation where he had low agency. His mother didn't respect his need to have dedicated utensils, and used his spoon for her cream of wheat, causing Alex to be sickened. His absence of agency ultimately caused him to move away from his parents into a home of his own. Agency is situational. For example, a person may have a high level of agency while at home, but have low agency in someone else's home, or other social situations. The absence of agency ideology is activated when a person is in a situation where they feel they are powerless to exercise or to assert their needs, or when someone mandates it's this way, "because I said so" without listening to alternative reasoning.

Exclusionary Etiquette

Exclusionary rules of etiquette powerfully impact people with gluten sensitivities. The exclusionary etiquette and the fit in at all costs ideologies go hand-in-hand. Mila (#10) narrates a situation she heard about in an airport where food was used to mitigate tension. She considers how, as a person with celiac disease, she would not have been able to participate:

There was a flight that was delayed, and it was right after 9/11, and somebody announced that there was a need for an Arabic translator at gate whatever and everybody got a little scared. And then the woman who stepped forward to be the Arabic translator discovered that it was an old grandmother who was visiting her grandchildren in this country, and she just needed help understanding what was going on. And not only that, but she had cookies. And before they knew it, instead of being afraid of this old Muslim lady, everybody was sharing her cookies. And I thought, ‘How wonderful it is that we can share the gluten-containing food to make it clear that we are all one people.' And I just thought, ‘if I had been there, I would've been hiding in a corner somewhere, and they would've thought that I was scared, or unfriendly.

Mila's story illustrates a social dilemma when one cannot explain a dietary issue because of a language barrier, and the lasting negative impression of refusing the food. Exclusionary etiquette ideologies mandate that we take what is offered to us, a cultural practice that implies goodwill and acceptance, even if we may suffer an autoimmune reaction to the cookie's ingredients. By not taking the cookie, she would risk offending the elderly woman. Taking a cookie would require that Mila handle gluten, and depending on her level of sensitivity, this gesture could cause devastating results. Alternatively, accepting a cookie and tucking it in a napkin to be discarded later would also present a risk of contamination. Rather than risking a social infraction, Mila may have felt it would be better just to take the cookie and suffer the consequences.

Exclusionary etiquette rules do not contemplate food sensitivities. Rather they require that guests should consume the foods offered by the host or hostess, as Vivian (#48) notes, "It is insulting to the host for the guest not to eat. It looks bad and makes people feel uncomfortable." This punctuates a long-held belief that cooking is a labor of love, and consuming the food means sharing the love. Consider the effort of bread making, a staple at most meals: mixing the dough, kneading, rising, punching down, forming it into a loaf, rising again, baking, and cooling. It takes several hours from start to finish. To reject the bread and, thus, the hours of labor can be a personal affront. Food preparation often symbolizes the mother's love for her family (DeVault, 1991). Cooking is rich in tradition and ritual, bringing to mind the women spending the holiday carefully preparing food for the festive dinner (de Certeau, et al., 1998, p. 153). The expression of love transfers from the food made by the women, to the food consumed by the loved ones. This sentiment is echoed by Riley (#65):

My mother-in-law made a bunch of different foods for Thanksgiving, and I couldn't eat it, and she was offended that I wouldn't eat anything but the ham … that was pretty much it. She didn't understand that I wouldn't eat the other foods [to preserve] my safety and my health.

In this example, long-established traditions override objective thought on the part of the mother-in-law, possibly "influenced by [her] own rhetoric of justification and by the ideological consolidation that prevailed" (Mills, 1962, p. 27). The mother-in-law's plans and expectations for the Thanksgiving meal were disrupted by the daughter-in-law's special needs. From the mother-in-law's perspective, she labored over the preparation of the meal, likely using recipes that were passed down in her family for generations that she hoped to give to her daughter-in-law. The mother-in-law's food preparation practice constituted an act of love that was rebuffed by her daughter-in-law. "We eat what our mother taught us to eat—or what our wife's mother taught her to eat" (de Certeau, et al., 1998, Loc. 3969); thus, rejecting the traditional foods implied non-acceptance of the mother-in-law's family, and a breach of traditional etiquette rules. When a guest in someone's home, we are expected to eat the foods offered by the hostess, and to compliment her on the foods. Refusing what is offered whether cake or tea, is considered an insult.

Rules of etiquette provide guidelines on how we ought to live. Not following them leads to punishment. As Dustin (#46) states, "If you don't eat the food provided by the hostess, you won't be invited back." Cara experienced this when she and her husband were not invited to a family function. When asked why they were not invited, her family member said, "Well, we're eating." For this reason, celiac disease can lead to a diminished social network. Dustin continues to explain that her in-laws no longer include she and her husband in dinner invitations. They told her, "We won't eat what you can't eat in front of you." This sentiment ignores the fact that there are many gluten free alternatives they could serve instead. The in-laws seem to emphasize what they want to eat over the social elements of a shared meal.

Rules of etiquette specifically dictate behaviors when handling bread at the table. When no bread plate is present, one is expected to place the piece of bread on the left side of the table (Baldrige, 1990). Crumbs on the left side of the table could cross-contaminate the neighboring diner who may have celiac disease. Bread is to be used as a tool to sop gravy or to move peas on a fork (Baldrige, 1990). If the breadbasket is sitting to your right, it is your duty to cut the loaf (holding it in the bread cloth) and pass it to the person sitting on your right (Baldrige, 1990). These rules could pose a dilemma for the person with celiac disease. First of all, it is considered impolite to discuss health problems at the table, so an explanation is impossible. Handling the bread, and having the crumbs from the basket fall onto the plate when passed would potentially contaminate the polite diner's plate. Finally, the person with celiac disease would have no way to sop gravy or to put peas on the fork, but after being contaminated with crumbs would likely elect not to eat the food on the plate at all. This poses another problem. Waiters do not typically take full plates back, even if the silverware is displayed in the "I'm finished" configuration. They may exclaim, "Is there something wrong?" Which, of course there is, but it would be rude to elaborate.

Summary and Sneak Peek at Future Chapters

This chapter discusses various ideologies and how they drive behavior. As you contemplate what you have read so far in Chapters 1 and 2, ask yourself, what ideologies or given "truths" do you and those around you live by? Are they serving you? Are they really true? How have your "truths" changed with your understanding of celiac disease and food sensitivities? Chapter 3 provides examples of how ideologies collide in public settings. Chapter 4 considers how the body is a battleground for those who live with food sensitivities that cause short- and long-term misery at the smallest infraction. We'll examine how society pressures us to have "perfect bodies." Chapter 5 brings the global, familial, and individual elements together to discuss the commensality (the act of eating in a social setting) conundrum. In Chapter 6, we'll examine how an individual adapts to a new definition of homeostasis. Chapter 7 discusses individual transformation, providing many examples from study participants of how lives were adapted to live gracefully with celiac disease and food sensitivities. Chapter 8 goes into detail on how to use the language of ideologies to affect a positive change with loved ones. The next chapter, "Share the Wealth" offers useful strategies offered by study participants on how to navigate life, and finally Chapter 10 discusses how we collectively can take action to change laws such as the American Disabilities Act, so our needs are accommodated more readily in restaurants and institutions. In sum, the book examines virtually all of the social aspects of living with food sensitivities and celiac disease.

Summary of Ideologies in Chapter 2

|

Ideology |

Description |

Chapter |

|

Reluctant Tolerance |

"I understand people have gluten intolerance, and those people annoy me." |

2 |

|

Gluten-Doubt |

"I don't believe you are that sensitive!" |

2 |

|

Able-Body Bias |

Where food served (anywhere) that does not consider those with sensitivities. |

2 |

|

Sorta "Scientific" |

Basing opinions on soundbytes that don't tell the entire story. |

2 |

|

I-Know-Best |

"My opinion about everything is "right" and you are "wrong." |

2 |

|

Exclusionary Etiquette |

Etiquette rules/expectations that may cause peril for those with special needs. |

2 |

|

Absence of Agency |

Where someone has no say, and when his or her special needs are not honored. |

2 |

|

Sacred Bread |

Bread is a sacred food, both for religious sacraments, and at the dinner table. |

2 |

Discussion Workshops with Dr. Duane

Join Dr. Duane in the step-by-step transformation process of living gracefully with food allergies. We start by identifying ideologies on several fronts that make life challenging. The first two chapters discuss broad global constraints impose by religion, the government, and other institutions. As we dig into future chapters, we'll learn how global beliefs translate into our interactions with friends and family, and with the way we think ourselves. By gaining a deep understanding of these "truths" or "beliefs," we can challenge them, re-strategize our responses, and ultimately transform and empower ourselves to live optimally with new "truths." Ultimately, participants will be equipped with ways to navigate the gluten-free, food sensitive lifestyle. These fee-based workshops are designed to help you take the concepts from the book and apply them to your life. Group sizes are limited to encourage enriching discussions. Awareness is the first step toward making a positive change. The next step is to have a plan, and finally to implement the plan. Please go to (www.alternativecook.com and click on Discussion Workshop Signup).

Forum Questions:

1. How have you experienced the Reluctant Tolerance, Gluten-Doubt, Able-Body Bias, Sorta "Scientific," I-Know-Best, Sacred Bread, Absence of Agency, and Exclusionary Etiquette ideologies discussed in this chapter?

2. What used to be "true" for you but isn't your "truth" anymore? How has that affected you and your relationships with those whose "truths" haven't changed?

Copyright © 2021 by Alternative Cook, LLC

Continue to: Gluten-Centric Culture: The Commensality Conundrum - Chapter 3 - Where Ideologies Collide In Public Settings

Back to: Gluten-Centric Culture: The Commensality Conundrum - Chapter 1 - Are You Kidding?

___

References in Chapter 2

- ABC. (2018). Jimmy Kimmel asks what is gluten? Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Health/video/jimmy-kimmel-asks-what-is-gluten-23655461

- Adams, K. M., Kohlmeier, M., Powell, M., & Zeisel, S. H. (2010). Nutrition in medicine: Nutrition education for medical students and residents. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 25(5) 471-480. doi: 10.1177/0884533610379606

- Althusser, L. (1971). Lenin and philosophy and other essays. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

- Anderson, C. A., Carnagey, N. L., & Eubanks, J. (2003). Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(5), 960-971. 960-971. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.960

- Baldrige, L. (1990). New etiquette for the 90s. New York, NY: Scribner.

- BBC. (2018). How many Roman Catholics are there in the world? Retrieved April 1, 2018 from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-21443313

- Bernard, O. (2016). Let's put an end to the gluten-free trend. Retrieved from January 18, 2019 from thepharmafist.com.

- Boyer, P., & Lienard, P. (2006). Why ritualized behavior? Precaution systems and action parsing in developmental, pathological and cultural rituals. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29, 595-650. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X6009332

- Brante, T. (1993). Reasons for Studying Scientific and Science-Based Controversies. In T. Brante, S. Fuller, & W. Lynch (Eds), Content to Contention. (pp. 177-192). Albany, NY: State U of New York.

- Charland, M. (1987). Constitutive rhetoric: The case of the peuple Quebecois. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 73, 133-151. doi: 10.1080/00335638709383799

- Collins, R., Martino, S., & Elliott, M., (2011). Propensity scoring and the relationship between sexual media and adolescent sexual behavior: Commenting on Steinberg and Monahan. American Psychological Association, 47 (2), 577-579. doi: 10.1037/a0022564

- de Certeau, M., Giard, L., & Mayol, P. (1998). The practice of everyday life, Vol. 2. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- DeVault, M. L. (1991). Feeding the family: The social organization of caring as gendered work. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Duane, J. E. (2018). The media encourages negative social behavior toward gluten-free dieters. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- Fahnestock, J. (1998). Accommodating science: The rhetorical life of scientific facts. Written Communication 15 (3) 330-350.

- Fasano, A., & Catassi, C. (2012). Celiac disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 267(25), 2419-2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1113994

- Fasano, A., & Flaherty. S. (2014). Gluten freedom. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Filloon, W. (2016). Anthony Bourdain hates your gluten-free diet. Retrieved August 25, 2018 from https://www.eater.com/2016/6/6/11866220/anthony-bourdain-interview-adweek-gluten

- Foust, C. R. (2011). Considering the prospects of immediate resistance in food politics: reflections on the garden. Environmental Communication 5(3), 350–355. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2011.593534

- French Today (2018). What to expect at a typical French wedding. Retrieved March 23, 2018 from https://www.frenchtoday.com/blog/expect-typical-french-wedding

- Gellner, E. (1978). Notes towards a theory of ideology. Retrieved from http://www.persee.fr/doc/hom_0439-4216_1978_num_18_3_367880

- Green, P. H. R., & Jabri, B. (2003). Coeliac disease. The Lancet 362, 383-391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14027-5

- Hall, P. (2005). Who do they think they are? Counseling & Psychotherapy Journal, 16 (1), 40-41. No doi.

- Healthline. (2020). Is Gluten Bad for you? Retrieved February 8, 2020 from https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/is-gluten-bad

- Hilton, C. (2016). Unveiling self-harm behavior: What can social media site Twitter tell us about self-harm? A qualitative exploration. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 1690-1704. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13575

- History of Apple Stack Cake. (2018) History of the apple stack cake. Retrieved March 22, 2018 from http://therevivalist.info/history-of-apple-stack-cake/

- Huesman, L., R., & Miller, L. S. (1994). Media violence in childhood. Aggressive behavior: Current perspectives, Edited by L. Rowell Huesman. Plenum Press, New York.

- Huesmann, L. R., & Taylor, L. D. (2006). The role of media violence in violent behavior. Annual Review of Public Health 27, 393-415. No doi.

- Hyman, M. (2013). Gluten and chronic diseases: the connection. Retrieved from: http://thejourneytogoodhealth.blogspot.com/2013/08/gluten-and-chronic-diseases-connection.html

- Hyman, M. (2013). Gluten and chronic diseases: the connection. Retrieved from: http://thejourneytogoodhealth.blogspot.com/2013/08/gluten-and-chronic-diseases-connection.html

- Jones, C. (2013). For them, not us: How ableist interpretations of the International Symbol of Access make disability. Critical Disability Discourse/Diseours Critiques dans le Champ du Handicap, 5, 67-93. No doi.

- Kinsella, B. (1997). The Oprah effect. Publishers Weekly, 244(3), 276-278. No doi.

- LeBesco, K., & Naccarato, P. (2008). Edible ideologies: Representing food & meaning. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Lee, E., & Kim. M. (2004). Exposure to media violence and bullying at school: Mediating influences of anger and contact with delinquent friends. Psychological Reports, 95(6), 659-672. doi: 10.2466/PRO.95.6

- Levenstein, H. (2012). Fear of food and why we worry about what we eat. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Levinovitz, A. (2015). The gluten lie: And other myths about what you eat. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Digital Sales, Inc.

- Mills, C. W. (1962). The Marxists. New York, NY: Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

- Montanari, M. (2006). Food is culture. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Moore, L. R. (2013). How non-celiacs changed gluten free: Reshaping contested illness experience in the gluten-free diet boom (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest, LLC (10290861)

- Myth. (2015). The myth of big bad gluten. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/opinion/sunday/the-myth-of-big-bad-gluten.html

- NBC News. (2016). More people go gluten-free than need to, study finds. Retrieved November 18, 2018 from https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/more-people-going-gluten-free-need-study-finds-n643931

- Nownes, A. J. (2012). An experimental investigation of the effects of celebrity support for political parties in the United States. American Politics Research, 40(2), 476-500. doi: 10.1177/1532673Xll429371

- Rohan, M. J. (2000). A rose by any name? The values construct? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 255-277. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0403_4

- Shanahan, C. (2017). Deep nutrition. New York, NY: Flatiron Books.

- South Park (2014). Gluten free ebola. Episode 2, Season 18, Directed by Trey Parker. Written by Trey Parker. Production code 1802.

- Taubes, G. (2016). The case against sugar. New York, NY: Knopf.

- The Spruce. (2018). Seven wedding cake traditions and their meanings. Retrieved March 5, 2018 from https://www.thespruce.com/wedding-cake-traditions-486933

- Therborn, G. (1980). The ideology of power and the power of ideology. London, England: Verso.

- Titchkosky, T. (2008). To pee or not to pee? Ordinary talk about extraordinary exclusions in a university environment. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 33(1), 37-60. No doi.

- U.S. Census. (2019). American population clock. Retrieved March 16, 2019 from https://www.census.gov/popclock/

- U.S. News. (2018). Health issues that are sometimes mistaken for gluten sensitivity. Retrieved November 15, 2018 from https://health.usnews.com/wellness/food/slideshows/health-issues-that-are-sometimes-mistaken-for-gluten-sensitivity

- USDA. (2015). USDA Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020, (8th Ed.). Retrieved October 1, 2018 from DietaryGuidelines.gov

- USDA. (2015). USDA Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020, (8th Ed.). Retrieved October 1, 2018 from DietaryGuidelines.gov

- Vatican. (2017). Letter to bishops on bread and wine for the eucharist. Retrieved from http://en.radiovaticana.va/news/2017/07/08/letter_to_bishops_on_the_bread_and_wine_for_the_eucharist/1323886

- Vetter, M. L., Herring, S.J., Sood, M., Shah, N, R., & Kalet, A. L. (2008). What do resident physicians know about nutrition? An evaluation of attitudes, self-perceived proficiency and knowledge. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 27(2), 287-298. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719702

- Villanti, A., Boulay, M., & Juon, H. (2010). Peer, parent and media influences on adolescent smoking by developmental stage. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 133-136. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.018

- Wedding. (2018). Wedding: Did you know that bread is part of a wedding tradition? Retrieved from http://www.weddingandpartynetwork.com/blog/wedding-traditions/bread-wedding-tradition/

- Yudkin, J. & Lustig, J. (Original 1972, updated by Yudkin in 1986 and reprinted 2013) Pure, white and deadly London, UK: Penguin Books.

- Zhou, S., Shapiro, M., Wansink, B., (2016), The audience eats more if a movie character keeps eating: An unconscious mechanism for media influence on eating behaviors. Appetite, 108, 407-415. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j-appet.2016.10.0280195-6663

Recommended Comments

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now