Celiac.com 06/03/2023 - This article first appeared in the Australian Coeliac newsletter, and is reprinted here by permission of the Australian Coeliac Society. By Robert Anderson, MD, Peter Gibson, MD and Finlay Macrae, MD.

In 2002, the diagnosis of celiac disease means an end to delicious French pastries and the casual approach to diet that most people in the community enjoy. Today, strict adherence to a gluten free diet is the only effective treatment for celiac disease.

A Vaccine for Celiac Disease?

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

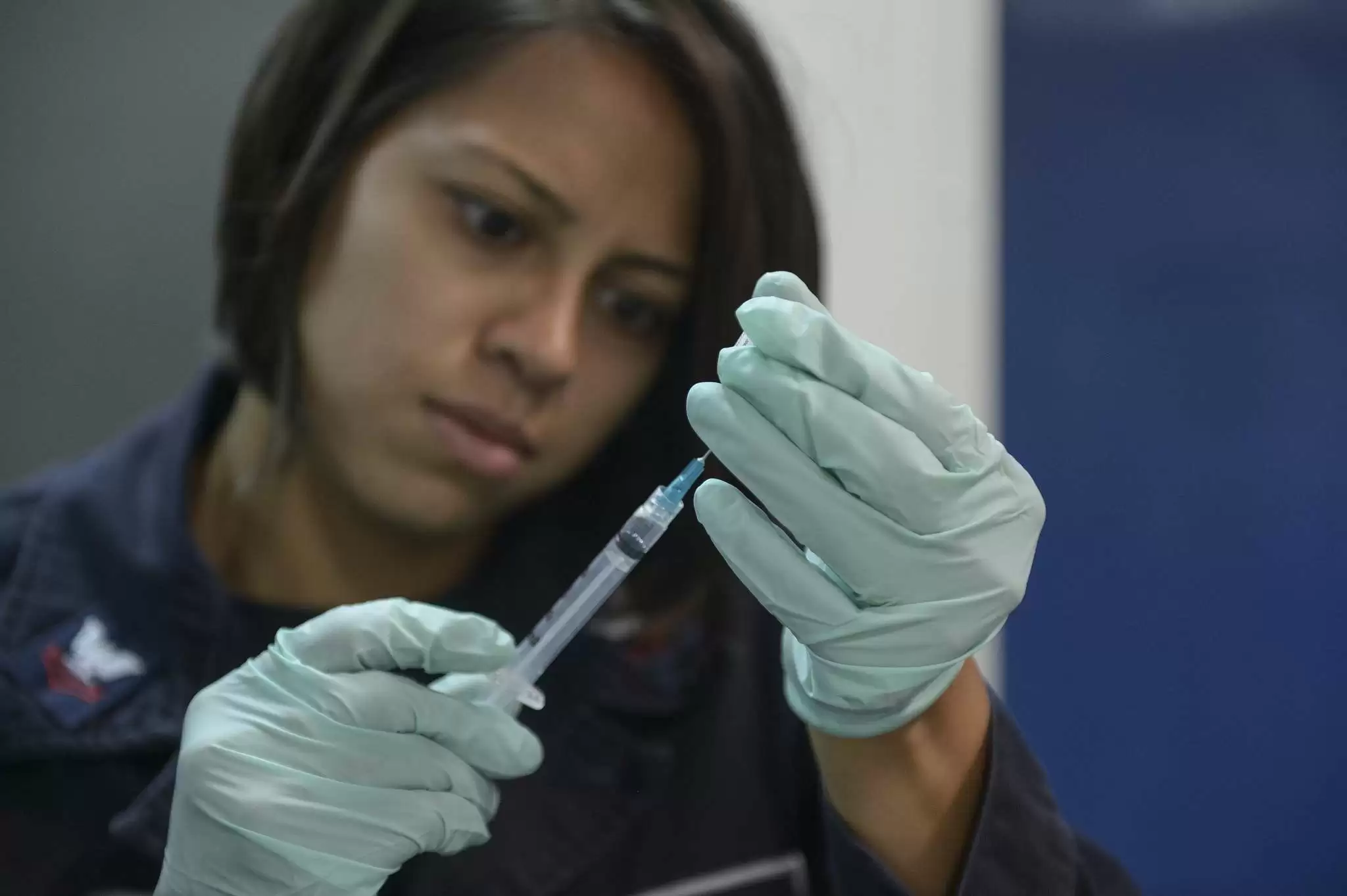

The good news is that new research in celiac disease suggests a "vaccine" may be feasible!

Such a development has come from a greater understanding of the cause of celiac disease. You might say that we have known the cause of celiac disease for decades—"something" in gluten. But, there is more! We are all exposed to gluten but only some of us get celiac disease. This other factor is the characteristic of the immune system that makes the small intestine a "battleground" when it is exposed to gluten.

The exciting advances are twofold. First, we have now identified the "something" in the gluten that makes the immune system angry (that is, the target of the immune response). Secondly, we now understand why only some people's immune system gets angry with gluten—it is all about the genes we carry that control the immune response.

How the Advances were Made

Almost all individuals with celiac disease have one of two genes involved in the immune response, HLA-DQ2 (90%) or HLA-DQ8 (5%). In the general population only 30% have one of these genes, let's call them A and B. These genes are also very common in early onset diabetes and thyroid disease (both quite commonly associated with celiac disease). A and B have the task of latching on to chunks of proteins (peptides) and carrying them to certain cells in the immune system called T cells.

In celiac disease, we know that gluten peptides are indeed taken ("presented") to T cells via A and B. Gluten peptides attached to A and B then activate a proportion of the T cells present in the gut and cause the flattening of the intestinal villi known as villous atrophy— the pathologist's hallmark for diagnosing the disease.

Ever since it was shown that gluten causes celiac disease, the challenge faced by researchers was to prove whether there are many, a few, or just one component of gluten that is "toxic"—that is capable of causing this damage. Most researchers thought that a wide range of components of gluten (peptides) were involved in causing celiac disease, and indeed a range of T cells reacting against various gluten peptides were found. This would have meant that the idea of a vaccine to abort this immune process to gluten (a process technically called "tolerance") was impractical.

However, these early experiments with T cells were unable to show what really happened when gluten was exposed to the immune system in "real people" with celiac disease. Our work performed in Oxford, and to continue at The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Box Hill Hospital and Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Melbourne, utilizes T cells from celiac subjects that have recently eaten gluten-containing bread. T cells induced by eating gluten could be measured in blood.

To our surprise, these T cells initially targeted only one small component of gluten (a small peptide) in the most toxic fraction of wheat gluten (alpha-gliadin). Whether different peptides in the other components of wheat, rye and barley gluten are targets to which T cells react in patients with celiac disease is currently under investigation.

How a Vaccine Might Work

In animal diseases, the understanding of how T-cells respond is much further advanced than in humans. In fact, it has been possible to prevent and even treat animal diseases caused by T cells by "vaccinating" with T-cell target peptides. For example, nasal administration of peptide can prevent a mouse disease similar to multiple sclerosis. It "blocks" the subsequent immune response which is the hallmark of the disease. Why can't we do this in celiac disease?

Celiac disease is the first human condition for which there is a clear understanding of the T-cell targets—a peptide in gluten.

In work that is now planned in Melbourne, the possibility of a "vaccine" for celiac disease will be tested. The first stage of this project will begin in the next six months. But even if successful, it is still likely to be ten years or more before a "treatment" is ready for general use. These studies may provide celiac disease with its first alternative to a gluten free diet. Welcome back French pastries and crusty bread!

Recommended Comments

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now