Celiac.com 03/30/2016 - The woman's voice, polite but firm came over the line: "We cannot accommodate your mother."

"You can't accommodate her?" I wondered if I'd heard wrong.

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

"No. We just had a team meeting and it was decided we cannot accommodate your mother because of her diet."

"Oh." The line hummed as I took in both the news and the woman's frosty tone. The previous week the woman, the admissions coordinator of the nursing home, had been all warm and inviting, even eager to have my mother.

Finally I came out with, "Well…thank you for letting me know," and the line clicked dead as the woman hung up.

I had not seen this coming. I hadn't realized that a nursing home would, or could, turn down a patient based on the need for a therapeutic diet. I thought the reason for a nursing home was to care for ill people.

When I toured the nursing home, the woman proudly proclaimed the facility as being on Newsweek's top recommended list, and gave the appearance of understanding my mother's gluten-free diet, saying, "My niece has told me of it. She's convinced me to eat more gluten-free." The woman went so far as to take notes on my mother's preferences, her love of sleeping in and drinking coffee, and then plopped in my arms a thick packet of Medicare forms. In all ways she had been exceedingly pleasant. Indeed everyone I met at the facility had been pleasant. Purring cats roamed the facility's hallways, birds sang from cages, and they even had a pot-bellied pig in the shade of a tree that could be seen through a window, all for the comfort of the patients. It struck me that they could do these many things for their patients, but feeding one small woman with celiac disease a gluten-free diet was beyond them.

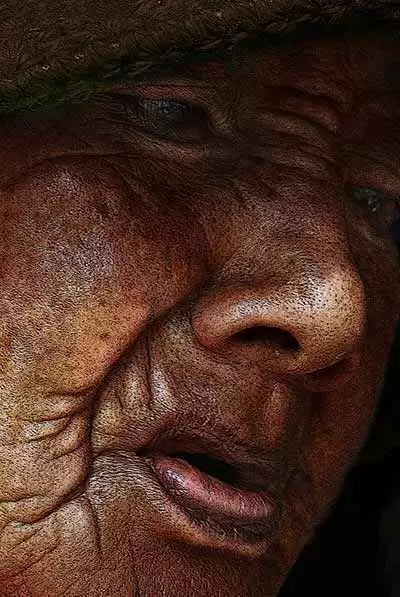

My mother is eighty-eight years old, a pixie with a contagious smile and genteel Southern manner. She was diagnosed with celiac disease at the age of seventy-five. At that time she was on daily use of a nebulizer, sleeping half days and could not leave home and the bathroom unless she took Imodium. The diagnosis and strict adherence to the gluten-free diet returned her to an active life. She took up painting and driving her aging neighbors out to enjoy shopping.

A year ago, in rapid succession, a mass was found in one of her lungs, glaucoma took her sight and a stroke impaired her right hand and memory. For months, she required caregivers around the clock. Today she is mobile with the aid of a walker and can manage nights on her own. She can do one thing for herself, and that is get herself to and from the bathroom. Everything else must be done for her—bathing and dressing and maintaining clothes, medications, food preparation, working the television and her bedside radio. On occasion she will get confused and afraid, so I try not to leave her alone for more than an hour. With the aid of private caregivers and hospice assistance, I have been able to keep her in my home, where she has lived for the past six years. However, her funds are depleting for private care, and there is no one to help me care for her.

After the disappointing phone call from the nursing home admissions coordinator, I sat thinking over all the above facts and allowing myself a sizable hissy fit. Then I gathered myself together and took another look at the nursing home facilities in my area.

For the next two weeks, I sought more information and made lists. My plan was to be better prepared in knowledge and approach. Running on the theory that it is lack of knowledge that causes the fear of a situation, I put together information on my mother: a list of her conditions, needs and food preferences. Because of no longer having teeth, nor wearing dentures, and her advanced age, she needs soft foods, her favorites being eggs and Vienna sausage, puddings, bananas. At the time she would eat mashed chicken and some vegetables, all simple things. I wanted to reassure the admissions director and staff of the nursing facilities that my mother was easily cared for, and that I was willing to help with her food. I also had two brochures from Gluten Intolerance Group: a single sheet on celiac disease itself, and a color glossy brochure, put together in cooperation with the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness, entitled Celiac Disease in the Older Adult. I hoped to engage the interest of people whose primary aim and business is providing healthcare to the elderly.

What I discovered is a general lack of any interest in the welfare of the elderly.

The young woman admissions coordinator of my second choice of facilities, a modern, airy facility, answered my question about their kitchen and possible meeting with the dietary manager, with, more or less, "I've shown you around the building. I don't know what else you want to know." Then she added, "And right now we don't have any female beds available."

At another facility, the admissions coordinator brushed aside any idea of speaking with the dietician. She did not know what celiac disease was, but assured me they could, "probably handle it."

The best facility that I found had a waiting list of at least forty names. They stayed so full that they did not provide temporary respite care. Even so, the admissions coordinator showed me around the building, which was very old, and the sight of an elderly blind woman slumped uncomfortably in a wheelchair in the hallway haunted me. Yet their menu posted on the bulletin board seemed promising. "We do home-cooking," the coordinator said proudly. Then she glossed over my request to see their kitchen and meet the dietician. She admitted to never having heard of celiac disease, but said, "We've had many people with uncommon conditions," and put my mother's name on the waiting list. My eye followed her fingers working the pen far down the yellow legal pad. When I offered to leave the brochures about celiac disease with her, she did not even glance at them, but dismissed them with a sweeping wave, saying, "Oh, there's no need."

Weeks passed. My mother's hospice social worker joined in on the search. She found a facility willing to give the respite stay a chance. "They've had a previous celiac patient," she said.

By now I was quite skeptical, but also curious with this news. The facility she suggested was the closest near my home, and I could easily visit each day. I agreed to meet with the admissions coordinator.

The woman said that, yes, the facility had had a previous patient with celiac disease. It was the experience with this patient, who had been uncooperative and would steal food off other patients' trays, that caused the hesitation on their part. "But we're told your mother wouldn't do that," she said.

Upon studying the fact that my mother was quite incapable of snatching food anywhere, the admissions coordinator said they were willing to offer respite care. I was impressed (surprised is the better word) when the coordinator called the dietary manager to meet me. He read the diet listing I had made up for my mother and said they would have no trouble in providing for her. I volunteered to bring her favorites of chocolate pudding and canned peaches and Vienna sausage for times they might have things she could not eat, and of course any homemade gluten-free cakes.

We packed my mother up, and she went for her week respite at the facility. Her long-time caregivers went as well to provide support in the strange environment, help her learn her way to the bathroom, and to circumvent the inevitable glitches.

The first day for lunch in the dining room, my mother was brought Vienna sausages (which I had provided), nothing else. My mother's caregiver went to the kitchen and inquired of the cooks, surveyed the kitchen and the menu of baked chicken and broccoli and how it was cooked and said, "She can have that." We began to wonder how the previous patient had been fed. I also began to wonder if anyone even glanced at the diet I had printed for my mother.

However, the glitches that week were small. My mother ate well, enjoying their broccoli and branching out to embrace canned spinach. We learned the main reason the facility could and did for that week, succeed in feeding my mother quite well was that they had a full working kitchen and did not rely on food service, where all the meals come prepackaged.

The respite week also worked because of my mother's private caregivers. They monitored the food and educated the kitchen staff. The dietary manager went so far as to voice his gratitude to one of the caregivers for helping them learn what my mother and could not eat.

While it appeared no one read any of the dietary information, over all the stay went well enough that a month later, I decided to try it for long term care. The plan was to have her private caregivers ease my mother through the transition for approximately a month, and then gradually reduce their hours, as the nursing home staff learned my mother's needs. We believed it possible to educate the staff.

The first week went fairly smooth, with a few expected glitches. After that, things went downhill. A semi-soft diet had been requested; this never materialized. My mother's food would be placed on her tray in her room, and left, covered. Either my mother's private caregivers or I had to come in and help my mother eat. Mom's private caregivers continued to mash any meat and large chunks of vegetables, such as sweet potato served still in the skin. They continued to intercept sandwiches on bread and dishes of cake and snack cookies left on her tray. Throughout all of this, my mother's caregivers or I consulted with the dietary manager and the kitchen staff. We thanked them for the good food when it came. We explained again what she could and could not have. We formed the habit of checking each day's menu and writing out foods from that menu that my mother could eat. The kitchen staff accepted these menus and taped them near the stoves. When there was nothing on the menu that my mother could or would eat, we suggested easy canned substitutions. Sometimes she got these substitutions, sometimes not.

Then came the day when I was told that for the evening meal my mother had been served a hotdog and fries of some sort, both too hard for her, or anyone, to eat. (Keep in mind we are paying for this food.) My mother's caregiver took her back to the room and served my mother her snack cakes and pudding I had provided. Her roommate shared in the cakes, because she had come in too late from her dialysis treatment to get dinner. Why her tray had not been saved for her, I have no idea. I had never seen this woman provided any sort of special diet, and she was both diabetic and had kidney disease.

The following morning I also I learned one of the kitchen staff responsible for following the therapeutic diet said to my mother's caregiver: "Oh, she doesn't need that diet. That's all made up."

I faced the fact that providing for my mother was too much trouble for the staff, and they were simply unwilling. My mother was never going to get the food nor the care in eating that she would require at this facility.

As of this writing, my mother is back home. Private caregiver hours have been drastically reduced. I am able to do this, for now.

Here are some chilling facts: Studies indicate that today in our country not only are the incidents of celiac on the rise in all age groups, but the median age for celiac diagnosis is just under 50 years of age, with one-third of newly diagnosed patients being over the age of 65.* (Celiac Disease in the Elderly, Shadi Rashtak, MD and Joseph A. Murray, MD)

This is the age group who are the primary caregivers for themselves and their parents. This is the age group who more often must undergo surgeries and stays in rehabilitation nursing facilities.

Couple the above figures with the fact that we are an aging population. At the current rate, the number of people age 65 and older is projected to double between now and 2050. The baby boomers, responsible for the great population growth, now average over the age of 65.* (An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States, by Jennifer M. Ortman, Victoria A. Velkoff, and Howard Hogan, U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau.)

These simple facts paint a picture of a growing challenge. We must be able to provide short and long term nursing home care for the many celiac patients around us today—my mother, myself, the number of over-60 celiacs I've talked to—as well as the tidal wave looming on the horizon.

In addition, we have other food intolerances on the rise, and we have the needs of those with diabetes and kidney disease and other conditions requiring dietary restrictions. At present, all of these people, not only those with celiac, are being overlooked and discounted.

I have no solid answers to this immense problem. I do have suggestions on things that can be started.

The celiac community must recognize and begin to talk seriously about the problem of dietary care in nursing homes. Printing up a glossy brochure with the advice to have the doctor write an order for a therapeutic diet is a start. We have to step out more aggressively with ways to educate and implement therapeutic diets in a real way. We have programs in place educating restaurants and the food industry. Let's get aggressive with the health industry.

Of course, my experience is that these facilities do not want to be educated. This is where legislation is required. We need to lobby for legislation that requires compliance in the nursing facility industry, in the same way that food labeling compliance was attained.

Further, we need to support the push for legislation for a required number of CNAs per patient in nursing home facilities. At present, there are laws only governing the minimum number of RNs required per patient in nursing facilities. * (Minimum Nurse Staffing Ratios for Nursing Homes, Ning Jackie Zhang; Lynn Unruh; Rong Liu; Thomas T.H. Wan, Nurs Econ. 2006;24(2):78-85, 93.) There are no mandatory minimums for the number of CNAs, the people who actually do the bulk of the patient care—those who would monitor a person's diet and help that person to eat. At present the nursing home facility is allowed to choose for themselves the number of CNAs they need.

I remarked to a friend that there were a number of camps for children with celiac disease, places the child could get away and enjoy and eat safely.

"Well, what about for the elderly?" my friend said. "It seems if they can do it for kids, they could do it for the elderly."

What about the elderly? This is our new challenge—to make certain those elderly people with food sensitivity needs are well cared for.

_sachs.webp.dc58185944ae9f96a743cf7d3b6fe94f.webp)

Recommended Comments