Celiac.com 01/18/2021 - I remember the exact moment I first heard of celiac disease. I was sitting on a bed at the University of New Mexico Hospital, on the phone with my dad. My seventeen month-old daughter Mikaela lay listlessly in a metal crib across the room. Her limbs were emaciated and her belly swollen from starvation, after over a month of food had passed through her completely undigested. At least three weeks had passed since she'd last walked. By the time we'd landed here, at our third hospital, she just laid and stared, too weak to sit up or even cry anymore. Only the frequent blood draws and IV needles elicited any reaction from her now—heartbreaking screams I often had to leave the room for. It was at one of these blood draws earlier that evening that I first heard the word "celiac" uttered, passed between the technicians and barely caught by my exhausted ear. On the phone with my dad later, I mentioned that blood draw, mentioning it mostly because it had been such a bad one—they couldn't find a vein, it had taken forever, and it seemed like they'd taken a lot of blood. I must have mentioned the word "celiac," though, because my dad called me back not long after to tell me to look up celiac disease. And there on the internet, in neat bullet points, Mikaela's symptoms were listed to a tee. By the time a doctor came in to tell us the results the next day, we already knew what the news would be. But we didn't realize at the time that Mikaela was no ordinary celiac patient.

The First Hospital

We were only two weeks into 2013, with a healthy sixteen month-old daughter, when we saw the first sign that something was wrong. It was January 19th, Martin Luther King Jr. Day Weekend, and we were in the small town of Chama, New Mexico, for a local ski race. My stepmom, Mary Ann, is in charge of the event, and after the usual busy months preceding the ski race, my family and I had had a fun and relaxing day in the mountains participating in cross-country ski events and playing with our bundled-up baby daughter.

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

Although Mikaela had a history of being a colicky baby, she had always had good energy and enthusiasm, and I remember this weekend being no different. After eating a spaghetti dinner that evening, my husband, Trever, picked Mikaela up and trotted her around the room in his arms. Mikaela laughed and laughed.

And then she threw up.

Afterward, she was in good spirits and clearly wasn't sick. My dad, Patrick, who has a medical degree, was sure it was related to the copious amounts of milk she'd drunk right before we'd left for dinner. Another family friend, who had a daughter three years older than Mikaela, told me these things happen to young kids, and oftentimes you never find out why. I was uncertain, but felt reassured.

That night, however, Mikaela had an episode of diarrhea so bad that it made a mess of her pajamas and crib. It was pure liquid, and contained entire chunks of grapes, complete with the peels. I was freaked out, but again, Mikaela had eaten lots of grapes the evening before, and I figured that combined with her upset stomach from the milk, she was just having some sort of brief stomach bug.

The three-hour drive back home was brutal. She had that same diarrhea at least twice more. And that night, she threw up again. Over the course of the next week, she threw up every night, usually in her crib, and continued to have diarrhea once or twice a day. And every time, there were undigested chunks of food.

Because Mikaela had no fever and no other symptoms of illness, I was convinced her problems were due to something she'd eaten. I spoke with a friend who'd had a baby with acid reflux and other allergies. The symptoms sounded similar, so I decided to take Mikaela off of dairy products for a week and see if anything changed.

The vomiting stopped, but the diarrhea didn't. It was at about this point, a week and a half after her first symptom, that she started losing energy. She was walking less, and I could tell she was losing weight. Still figuring it was a bad stomach bug, or something she had eaten that was disagreeing with her, I brought her to the doctor, expecting to be told she'd get better in a few days and maybe be sent home with a prescription.

Instead, she was sent to the hospital with severe dehydration and low blood sugar (34). She had dropped almost a pound since her last weigh-in two months earlier, to 18 pounds. Once she was at the hospital and hooked up to an IV, she cheered up again. The hospital gave her a stuffed animal she loved, which we affectionately named Doctor Hops, and we saw her smile again for the first time in a week.

The week before her first hospital stay, it had been increasingly hard to find foods Mikaela would eat. At 17 months old, she was learning that food was hurting her, and already becoming afraid to eat it. Ironically, and sadly, she was living almost exclusively on saltines and graham crackers—very high sources of gluten that were unknowingly just making her sicker. But with her weight loss and her increasingly sensitive stomach, Trever and I were just happy we could get her to eat anything at all.

At the hospital, they had little cups of vanilla ice cream that Mikaela fell in love with. Because I figured Mikaela's problem had been dehydration and low blood sugar, I let her eat them. She continued to have diarrhea in the hospital, which the doctors assured me would clear up soon, but she didn't throw up again so I figured the ice cream was in the clear.

I was wrong. Almost as soon as we arrived back at our house, two days later, she threw up again. Alarmed and scared, I called the hospital back right away. They thought she might still be having a reaction to dairy, and told me it was most likely a result of all the ice cream she had eaten. They told me to keep an eye on her and call my doctor back if it continued.

After I hung up the phone, I saw that Mikaela was back in good spirits after Trever had cleaned her up, so I knelt down and held out my arms. Mikaela tried to walk toward me. She was still so weak she only managed about three steps before falling and hitting her head on the kitchen floor. It would be the last time I'd see her walk for over a month.

The Second Hospital

It was at this time, between the first and second hospital visits, that I found out I was pregnant with my second child. Trever and I had long been excited about giving Mikaela a little sibling, but right now, with our first child so sick, it was hard to even think about a new child growing while the other one declined. I remember going in for a blood test and telling the nurse that my daughter, sitting in her stroller, had been sick, saying it like it was an ordinary thing but knowing in my heart that it wasn't.

Our chief focus the week after Mikaela's release from the hospital was making sure she drank enough that she wouldn't end up back there. Mikaela and I visited her pediatrician every other day, often spending over an hour waiting to be fit in around the normally-scheduled patients. Mikaela, completely uninterested in walking and growing steadily weaker, would sit listlessly in my lap. I spent our time taking selfies of us together, doing anything I could to wring a smile out of her again. In less than three weeks, I could see barely a shadow of the vibrant baby we'd raised.

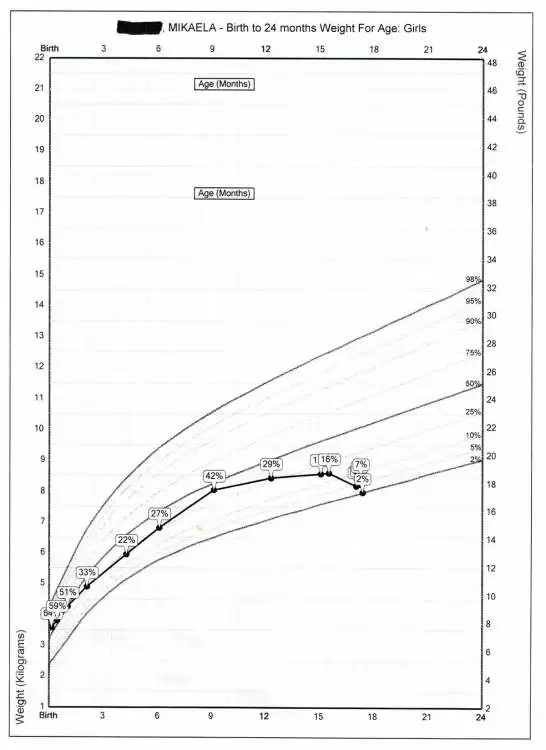

Her growth charts showed a decrease of weight from her regular visit two months earlier: she had dropped from 15th percentile to 2nd. But one thing alarmed her doctor even more. Neither her height nor her head circumference charts showed any growth for the last four months, since she'd been 13 months old. The doctor wanted Mikaela to see a neurologist for her walking and an endocrinologist for her growth. More than anything, I remember feeling intense frustration that the doctor was fixated on this growth issue when Mikaela was so sick. I just wanted her to be healthy again, and thought we could figure out the growth charts afterward. With everything going on, it never occurred to me that this was an abnormal or serious issue.

At her appointment that Friday, her doctor decided we could no longer wait to send her to a neurologist, because for a baby to stop walking for this long meant something serious was going on. She sent her to a different hospital. A neurologist tested her reflexes and declared that nothing was wrong with her legs. A doctor took an x-ray of her belly, which was now noticeably swollen from her constant diarrhea, and told us Mikaela was very constipated. They did an enema. It was a miserable process, and there was no noticeable improvement afterward.

The second day at the hospital, I brought her to the playroom, hoping to rekindle her interest in playing, and propped her standing at a play table. Then, as she became half-heartedly distracted by the toys, I backed slowly away to see if she'd remain standing on her own. She did, but it was less than a minute before she turned and saw that I'd moved. A look of fear flashed across her face, and her legs buckled beneath her. Whatever was going on with her, I knew it was far from "common."

A doctor witnessed the event in the playroom, and Mikaela was taken for an ultrasound of her hips. There was some excess fluid in one of them. Mikaela was diagnosed with toxic synovitis—built-up fluid in the hips after a virus, which can sometimes affect walking. Reassured that they'd figured out what was wrong, the doctors told me it should clear up on its own within five days, possibly faster if we gave her infant Ibuprofen. Once again, Mikaela was sent back home.

The Third Hospital

Although the new diagnosis gave me hope at first, we saw absolutely no sign of improvement. In fact, Mikaela continued to get worse. She was painfully thin, with a protruding backbone and ribs. Her belly was so distended that she looked pregnant. Her cheekbones stood out sharply in her face. Her energy was nonexistent. She could no longer pull herself to a sitting position or grab my finger within her fist. She basically didn't move except when I carried her.

For the first time, I began to fear she could actually die from this. But I felt the hospitals had done all their tests, and I didn't know what else they could do if I brought her back. I was torn apart by the terror and helplessness of the situation. Another thing that worried me was that we were on the cusp of a holiday weekend (President's Day), and I knew that it would be more difficult to get in and see her doctor if we had an emergency where she stopped breathing or something. I called my dad, who had visited the previous week and seen her condition. He felt as helpless as I did, but told me that after he ‘d related her story to a friend who'd lost a baby to SIDS, the friend had said, "That child needs to be in a hospital." I spoke to my best friend and she told me something that has stuck with me ever since: "You are her champion. You are the one who has to fight for her. You're all she has."

When I hung up the phone, I knew what I had to do. I was going to bring her back to the hospital, this time on my own terms, and I wouldn't allow her to be discharged until we had a correct diagnosis and could see her health improving.

It was 3:00 p.m. on Friday when I called her doctor's office and told them I needed to check my daughter back into the hospital. Her regular doctor was out of the office, but a different doctor called me back and said he'd sent Mikaela's info along to the UNM Hospital Pediatric ER, and to take her straight there. I showed up at the new hospital with Mikaela in my arms early Friday evening. Trever finally caught up with Mikaela and I in the ER waiting room, surrounded by the victims of that year's particularly bad flu season. Mikaela, too weak to fuss or cry, just lay in my arms amid the constant coughing and sneezing.

Mikaela was checked in, and a couple doctors came to talk with us. I described the past three weeks as best I could. "I brought her to the doctor because she'd been having diarrhea for over a week. We kept seeing the doctor the week after her first hospital stay because she still wasn't walking." At one point, one of the doctors stopped me and said, "You can stop justifying everything, because this is all very unusual." The other doctor told us that we had finally come to the right hospital, because he said being a university hospital with actively studying interns, they got all the weird cases.

The night that followed was a long one. Since the hospital was completely full from flu season, Mikaela and I were stuck into a space the size of a closet, with barely enough room to squeeze between her hospital crib and my bunk. In the middle of the night, one of the doctors from earlier returned with her growth charts, which he'd gotten from her records. He said, "I can't understand why either of those hospitals would have released her without addressing why her growth charts look like this." Mikaela was seventeen months old, but she'd basically stopped growing at twelve months.

We were moved again in the early hours, to a curtained-off section of a room where a baby coughed horrendously the whole morning and I sat half-comatose in a chair next to Mikaela's crib. Occasionally, I'd pull Mikaela out of her crib to hold her, but she didn't react in any way. She dozed on and off, but it was hard to tell, because she didn't act any differently awake than when she was asleep. We tried to keep her hydrated and to feed her, but anything we gave her almost automatically came out again through her diaper.

The next day, Mikaela was all over the hospital for testing. My mom had joined us, and tried to comfort me. My dad, who lives three hours away, kept calling to check on her and suggest tests to run and tell me what to say to the doctors. "Tell them she's starving to death," he said. At this point, sleepless and scared out of my mind, I heard an accusation in his tone that we had somehow caused this by not feeding her enough or feeding her the right things. It was an accusation that didn't exist—my dad was simply laying out the truth, and was as scared as I was—but I felt overwhelmed and sick from my pregnancy and couldn't deal with it anymore. I hung up the phone. I cried and cried.

Mikaela went through two MRI's and a lumbar puncture. One thing they suspected was a brain tumor, and they also wanted to see if anything was wrong with her spine. Not only was the strength in her arms and legs gone, but she had absolutely no reflexes in her legs, which convinced the neurologists something was wrong with them. The tests found nothing wrong with Mikaela's brain or spine, but one doctor suspected a condition called Guillian-Barre, which can sometimes affect walking after a virus. But the tests weren't conclusive, and the symptoms didn't quite match up.

My dad and stepmom joined us at the hospital. My dad was very apologetic, explaining that he never once meant her condition was due to anything we had done. I told my mom and dad about my pregnancy, and they and my husband helped out by accompanying Mikaela to the tests my pregnancy kept me from being present for.

Over the next couple days, as test after test was run and Mikaela's IV's were changed out and unending blood tests were taken, Mikaela continued to get worse. Nurses would come in to weigh her every few hours. Her weight had dropped below 17 pounds, and we struggled to raise it again. Her magnesium, potassium, and folate levels were dangerously low. The diarrhea was constant. On our third day at the hospital, Mikaela puffed up like a balloon. The change was startling after her emaciated state. The doctor grimly told us it was a result of low albumin—a protein made by the liver. Albumin normally helps keep fluid in the bloodstream and out of other tissues, but in cases of severe malnutrition, like Mikaela's, the fluid escapes the blood and causes the body to swell. Mikaela's body had used up all its glycogen, all its fat, all its stored protein and its muscles. I didn't know it at the time, but this intense swelling is one of the last stages of starvation.

On our fourth or fifth night there, with Mikaela barely clinging to consciousness, a team of techs came in and took one of their longest blood draws yet. They took blood at all hours, and part of me just wanted Mikaela to get some rest, but I was also afraid every time she closed her eyes that she wouldn't open them again. This blood test was so disruptive and late in the evening that I felt the need to recount it over the phone to my dad, somehow passing along that barely-snatched word I'd heard during the cacophony: celiac. It wasn't long after that he called me back and told me I needed to look up celiac disease.

So I did. And it wasn't like toxic synovitis or Guillian-Barre, where it was a stretch to make the symptoms match. I knew instantly what I was looking at.

I was looking at Mikaela.

The Diagnosis

Any Google search will show you what I found. Chronic diarrhea. Abdominal pain. Vomiting. Bloating. Fatigue. Decreased appetite. Weight loss. Failure to thrive. By the time a pediatric gastroenterologist came in the next morning, my whole family was waiting, sure we knew what the news would be.

It was almost the first thing out of the doctor's mouth: "I think she has celiac disease." The blood tests not only confirmed the diagnosis, but hinted at how severe her case was. Non-celiacs have only a small amount of antibodies called tissue transglutaminase (or tTG's) floating around in their blood—usually at a level of below 20. Mikaela's tTG level was somewhere over 250—off the measurable charts. In a person with celiac disease, the body turns gluten into a protein that attacks the small intestine. Mikaela had stopped growing at the age of 13 months, shortly after she quit breastfeeding and was introduced to gluten for the first time. Amazingly enough, she didn't drastically start to decline for another two and a half months, when her lack of nutrients finally caught up to her and started shutting her systems down.

When the pediatric gastroenterologist took a biopsy of her small intestine, he found that the villi inside lay completely flat, no longer able to catch and digest food. Not only did Mikaela undoubtedly have celiac disease, she was at the end of the spectrum for the most severe cases.

She was taken off gluten immediately, and the doctors worked on getting all of her vitamins and nutrients back up. We knew it might take a while to start seeing improvements. But we were shocked. Within 24 hours of being off gluten, Mikaela was making eye contact again. Within three days, she had already regained enough strength to pull herself to sitting. I remember the first time we saw her smile after a month of listlessness. One of the nurses had a light-up dinosaur on her lanyard, and Mikaela reached out for it with a tentative smile. It was the most beautiful thing I'd ever seen. She was showing interest in the world again. And four days after her diagnosis, Mikaela took a couple shaky steps across the hospital playroom on legs so skinny, they didn't seem capable of supporting weight. Our daughter was coming back to us.

Mikaela was discharged from UNM Hospital after just over two weeks. Although she still suffered from diarrhea and low weight, she was walking again, smiling again, and in improving health. Trever and I were certain she would fully recover within the next few months on the right diet.

It was true we wouldn't face the same level of decline that had almost killed her at 17 months. But Mikaela would face unexpected complications with her celiac disease over not just the coming few weeks…but the next several years.

The Aftermath

That summer was a rocky one, in terms of her health. Mikaela remained dairy-free for the next several weeks. Her baby brother grew bigger in my womb. We sold our house and lived with my mom for a month and a half as we waited on our new house to pass inspections. We're not completely sure to this day, but we think Mikaela ate a piece of cat food (which is very high in gluten) around the time we moved in. For the next month, we fought diarrhea so bad it threatened to put her back in the hospital. But she still had frequent doctor's appointments, and through careful monitoring and hydration, we managed to keep her healthy enough. She regularly saw a developmental counselor, who helped her get back on track after her delay. She still hadn't started growing again, and her belly was still very distended.

On the plus side, her tTG's were on the charts by July—from greater than 250 to 167. Another antibody that had tested very high at the time of diagnosis—deamidated gliadin antibodies, or IgA's—had fallen from 60 all the way to <.2. This number, at least, read perfectly normal now, and was a pretty clear indicator that we were successfully keeping gluten out of her body.

By September, when she turned two, her growth charts had finally started showing improvement in her height as well as her weight. She was also able to tolerate dairy again, and her diarrhea was under control. Her little brother Alexander was born in October. After our scare that spring, we felt truly lucky to have two healthy children in our lives.

But when she took her blood test a month later, we were shocked to find out that her tTg antibodies had gone up again—all the way back off the charts. Her doctor was puzzled, but Mikaela was healthy and her diarrhea was gone, so he chalked it up to the fact that sometimes those numbers take a long time to normalize. Only a few months later, he left UNM Hospital, never realizing that Mikaela was going to be a unique case.

We were delayed by the position being refilled, and waited to see if Mikaela's blood work would come down on its own. But a year later, the tTg's were still off the charts, even though her iGa's remained promisingly low. Her stomach was still distended, and by this time, we'd passed it off to a body type issue and hardly noticed it anymore. In April 2015, the new doctor, a pediatric gastroenterologist from England, decided to take another endoscopic biopsy to see if the inside of her small intestine was showing improvement.

The results weren't as good as we'd hoped. After almost two years on a gluten-free diet, the villi in her small intestine had gone from severe blunting to moderate blunting. It was clear that a normal gluten-free diet wasn't sufficiently healing her.

The doctor brought up a possible diagnosis of refractory celiac disease. This is a rare form of celiac that is resistant to a regular gluten-free diet. 1% of the population is said to have been affected by celiac, and refractory celiac disease only affects about 1% of those diagnosed. Not only was this strain of the disease rare, but it's virtually unheard of in children. It can also be a very dangerous diagnosis; there are two types of RCD, and one of the types leads to cancer. Fortunately, Mikaela's bloodwork suggested that even if she did have RCD, she wasn't likely to have the second type. However, even the doctor doubted this diagnosis, because patients who suffer from RCD are in poor health and have trouble keeping their weight up. Mikaela clearly didn't fit this profile.

Even though Mikaela was healthy on the outside, the doctor was concerned that leaving her small intestine that damaged could cause her health problems later in life, and even increase her risk of cancer. She wanted to start her on a steroid that would suppress her immune system and allow her gut to heal. I was very reluctant to put my healthy three year-old daughter on steroids, and suggested we cut back her diet to eliminate even the slightest chance of gluten cross-contamination. The doctor agreed it was worth a shot, so Trever and I proceeded to cut all processed foods out of Mikaela's diet. This meant grinding our own flour out of rice at home, making oatmeal from nuts instead of oats, buying only uncured meats, and no longer purchasing foods with more than four ingredients, to name just a few changes.

It wasn't an easy diet to adjust to, but with the help of paleo cookbooks and my dad's excellent cooking skills, we were able to find a variety of recipes and foods for our family. We were fortunate that Mikaela was a non-picky eater, and adjusted to these dietary changes with no fuss. Outwardly, we saw no changes; she appeared to be a strong and healthy young girl with a big tummy and a vivacious attitude.

After six months on her new and stricter diet, Mikaela's tTg levels were still off the charts, and she was put on iron for perpetually low ferritin levels. The doctor decided to give her another half-year to show improvement, but when labs were taken again in May 2016 and her levels remained the same, she put Mikaela on a six-month stint of corticosteroids called Budesonide. As I'd dreaded, she became aggressive toward her younger brother, and more disagreeable with us. She was constantly hungry and started retaining water, which made her body and face appear puffy and bloated. I hated the steroids just as much as I'd feared.

They did succeed in reducing the tTG antibodies, but it was slow and painful progress. After three months, they were down from over 250 to 208, then at six months, they were at 161. It had taken six months of steroids to get them as low as they'd gotten on their own shortly after her diagnosis, before they had climbed again. So what had changed?

Another biopsy was done in December 2016. There was improvement over the one from April 2014, with only mild villous blunting now. With her prescription for Budesonide done, the doctor decided to see if she'd continue improving without the steroids. But sadly, by August of 2017, the tTG numbers had soared off the charts again. I was really upset by the news, sure this meant the doctor would see that steroids were the only thing that worked and put Mikaela back on them.

It was at this time that UNM Hospital hired a gastroenterologist who specialized in celiac disease. At our first appointment with him, he took one look at Mikaela and said there was no way she needed to be on steroids. She was entirely too healthy. Unconcerned, he spent another year monitoring her bloodwork then decided to schedule another biopsy to see how things looked. It was clear that despite her high numbers, he expected to find nothing wrong based on her great outward health.

But this was not the case. Her small intestine still had villous blunting. When he called to tell me the results, he asked some questions about her diet, especially now that she'd started kindergarten. But I could tell in his voice that he didn't think the answers lay there, since she'd struggled with this for over four years now.

My doctor called me back a few weeks later to say he'd met with another celiac expert from the University of Chicago, named Dr. Guandalini. Reassuringly, this doctor had met other rare patients like Mikaela—asymptomatic on the outside, but not fully healing on the inside. He told my doctor that a dairy-free diet had helped in these cases. So we decided it was worth a shot.

As with every other step we'd taken, we didn't expect to see any differences outwardly. But I noticed, quite by surprise a couple months after starting the diet, that the distended belly she'd had since her diagnosis at 17 months was gone. The first thing I thought was that it was due to her taekwondo or other physical activity. But Mikaela has always been an active child, ever since she felt good again, and the difference in just two months was dramatic. Until that point, I'd never even considered that her stomach was related to her celiac disease, or thought much about it at all beyond thinking it was just the way she looked.

A month later, she went in for another blood test. I was optimistic that the outward change would mean her tTG's would be below 250 again—maybe even as low as they'd been on steroids, in the 160 range, even though it had only been three months. When I called the nurse, the first thing she said was, "Her tTG levels seem to be elevated. Has she been exposed to gluten?" I said, "How high are they?" She said, "49." I almost dropped the phone. Her antibodies had fallen by over 200 in three months! At long last, we finally knew why her numbers had dipped briefly in the aftermath of her diagnosis before climbing back up again—it was because we'd reintroduced her to dairy. Either because of the destruction in her gut from the gluten, or because it was something else she'd been born with, this intolerance to dairy had been keeping her tTG levels extremely high and keeping her from fully healing.

Mikaela has been gluten-free for seven years now and dairy-free for two and a half years. She is healthy and thriving, and rarely has stomach issues at all anymore. She had another endoscopy just last month, and everything came out perfectly normal for the first time in her life.

The diagnosis of Celiac disease saved her life, and I will forever be grateful to the doctors at the University of New Mexico Hospital who figured it out in the nick of time. Mikaela lives a full life now, thanks to everything we've learned since that day back in 2013.

Recommended Comments

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now